- BY ILPA

Brexit and the Common European Asylum System

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The UK Referendum on the EU and the Common European Asylum System

By Elspeth Guild, Partner, Kingsley Napley, 29 April 2016

Introduction

The issues of refugees’ arrival, reception and protection have been particularly evident in the political debate in the UK and elsewhere in the EU over the past six months. The images of people fleeing Syria and Iraq and travelling across Europe searching for a place of safety have touched the hearts of many. The obstacles and state action designed to prevent refugees from arriving in safety in Europe has also attracted much criticism.

One way to deflect the unease which many people in the UK feel about the treatment of refugees in Europe, including those trying to get to the UK camped in filthy conditions in Calais and other French ports, has been to blame the EU for the problem. This note sets out a short history of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) and the most recent reliable data on the arrival of asylum seekers in the EU in 2015.

What is the Common European Asylum System?

The CEAS has its roots firmly in the EU’s 1992 project designed in the mid 1980s to complete the internal market by abolishing border controls on the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital. It is this 1992 project which forms the basis of the Schengen area without internal controls on the movement of people. Concerns were expressed by interior and home affairs ministries of the then Member States in the 1980s about the abolition of border controls—in particular as regards asylum seekers and refugees. As a compromise to address these concerns, the EU agreed that asylum seekers and refugees would be excluded from the right to free movement without controls on persons. Instead they would be subject to a specific regime which would require them to apply for asylum, in practice, in the first Member State through which they arrived. This is generally called the ‘Dublin’ principle after the city in which the first agreement was signed.

Also in the early 1990s, the Member States agreed among themselves a series of issues including:

- the definition and rights of refugees and beneficiaries of international protection

- procedures for determining applications and principles of safe countries of origin, and

- safe third countries for asylum seekers to be returned to.

It was not until 1999 that the CEAS was actually created through amendments to the EU treaties to give the EU institutions competence over asylum. At that time, the UK negotiated a right to opt out of any binding legislation of the CEAS which it chose not to apply, but it could only opt out once, and could not opt in and then out.

With the creation of the CEAS, the EU entered into the field of asylum which was already heavily populated by international obligations which all Member States had accepted. The first is the UN Refugee Convention 1951 and its 1967 Protocol which prohibits states from sending a refugee (including an asylum seeker) to a country where he or she would be at risk of persecution. Thereafter, the UN Convention Against Torture 1984, again ratified by all EU Member States prohibits sending anyone to a country where there is a real risk that he or she would suffer torture. In 2006 the UN adopted the Convention Against Enforced Disappearances which also prohibits sending anyone to a country where there is a real risk that he or she would be subject to an enforced disappearance. Almost all Member States have signed and many have ratified this convention. The European Court of Human Rights interprets the European Convention on Human Rights as also prohibiting the sending of anyone to a country where there is a real risk that he or she would suffer torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. So the CEAS has to be consistent with the obligations which the Member States already had, and further, according to the EU treaty, it must be consistent with the UN Refugee Convention (with regard to the guidance of the UNHCR on its proper implementation).

The first phase of legislative activity of the CEAS was completed in 2005 by which time four key measures had been adopted:

- the Dublin Regulation setting out the rules around which asylum seekers would be allocated to Member States for processing of their asylum applications—to make the Dublin Regulation work, the EU created a database of the fingerprints of all asylum seekers (EURODAC) in order to be able to check where they ought to be

- the Reception Conditions Directive setting out the minimum standards of reception (housing, support, health care etc) which states must provide to asylum seekers.

- the Qualification Directive defining the status of refugee and beneficiary of subsidiary protection and the rights which attach to each of the statuses, and

- the Procedures Directive establishing the procedural standards which much apply to the determination of all asylum applications.

The UK opted in to all these measures and transposed them into national law. In 2013 the EU agreed the second phase of the CEAS moving from minimum standards to common standards in all four areas covered by the measures adopted by 2005. The UK opted out of all of these re-cast measures with the exception of the new Dublin Regulation. But it remains bound by the first phase measures. The reason why the UK opted in to the first phase measures was that the government of the time considered that this would be in the UK’s best interests. By the time the second phase measures were negotiated, the UK government had changed and there was no longer a consensus that participating in further EU integration on asylum law was advantageous for the UK.

The CEAS has been much criticised by practitioners and academics as being too harsh on asylum seekers. The Dublin system in particular has come in for consistent criticism as it creates uncertainty and hardship for the asylum seeker who may have good reasons for wanting to make his or her asylum application in a country other than the one which is designated under the EU rules—such as the individual who arrives in Greece but has close family members in the UK. The same issue arises in respect of people stuck in Calais who do not want to apply for asylum in France as they have family and other links in the UK. They fear that if they apply for asylum in France it will be a very long time, if ever, before they will be able to join those family members in the UK. The person then is threatened with removal to another Member State where he or she does not want to be and is prohibited from applying for asylum where he or she does want to be. Although the European Commission has calculated that in practice only 3% of asylum seekers are ever subject to a Dublin transfer, the threat affects many asylum seekers negatively.

The UK government is a strong supporter of the Dublin system, not least as it results in few asylum seekers being entitled to apply for asylum in the UK because its geography is far from the entry points through which asylum seekers enter the EU. Thus the chances are very good that some other Member State will be responsible for the asylum seeker before he or she gets anywhere near the UK. This is the issue of the so-called Calais jungle where people who want to apply for asylum in the UK are required by the EU rules to apply for asylum in France (where they do not want to be). Although there is much speculation about why asylum seekers want to apply in one Member State rather than another, under EU law they are entitled to the same conditions of reception during the process of determining their claims, and the same rights (work, education etc) when they are recognised as refugees or beneficiaries of international protection. So there is no objective reason based on benefits for an asylum seeker to want to make an application in one Member State rather than another.

The problem of people drowning in the Mediterranean on their way to seek asylum in the EU is not one directly related to the CEAS. Instead it is the result of EU (including the UK’s) border controls. People in need of international protection generally cannot take scheduled flights to Europe as they do not have the necessary passports and visas. Without these documents the carriers will not allow passengers to embark, as the carriers will be fined on arrival. Thus the only option for people seeking asylum in Europe is frequently to place their lives in the hands of smugglers—the only ‘travel agents’ who will deal with them. Having created the problem of death in the Mediterranean through border control rules, the EU has then set out trying to save people from drowning in the Mediterranean using coast guards and military assets.

Outcomes of the CEAS and the possible consequences of UK withdrawal

What are the outcomes of the CEAS? The first problem is that for asylum seekers there are still very substantial differences in protection rates depending on where they have applied for asylum in the EU. This is the case even for asylum seekers from war-torn countries where the asylum claims are primarily on the basis of the generalised violence in the country of origin.

Refugee Recognition Rates by selected Member State and country of origin: 2013/14[1]

Afghanistan

| % of (EU) applications[2] | % given protection | |

| Germany | 7 | 67 |

| UK | 8 | 14 |

| Netherlands | 2 | 50 |

| Austria | 25 | 98 |

| Denmark | 6 | 37 |

Iran

| % of applications[3] | % given protection | |

| UK | 8 | 57 |

| Germany | Not available | 73 |

| Belgium | Not available | 61 |

| Austria | 3 | 97 |

| Netherlands | Not available | 45 |

Iraq

| % of applications (2014)[4] | % given protection | |

| Germany | 6 | 87 |

| UK | Not available | 37 |

| Sweden | 10 | 52 |

| Netherlands | 4 | 42 |

| Austria | 19 | 97 |

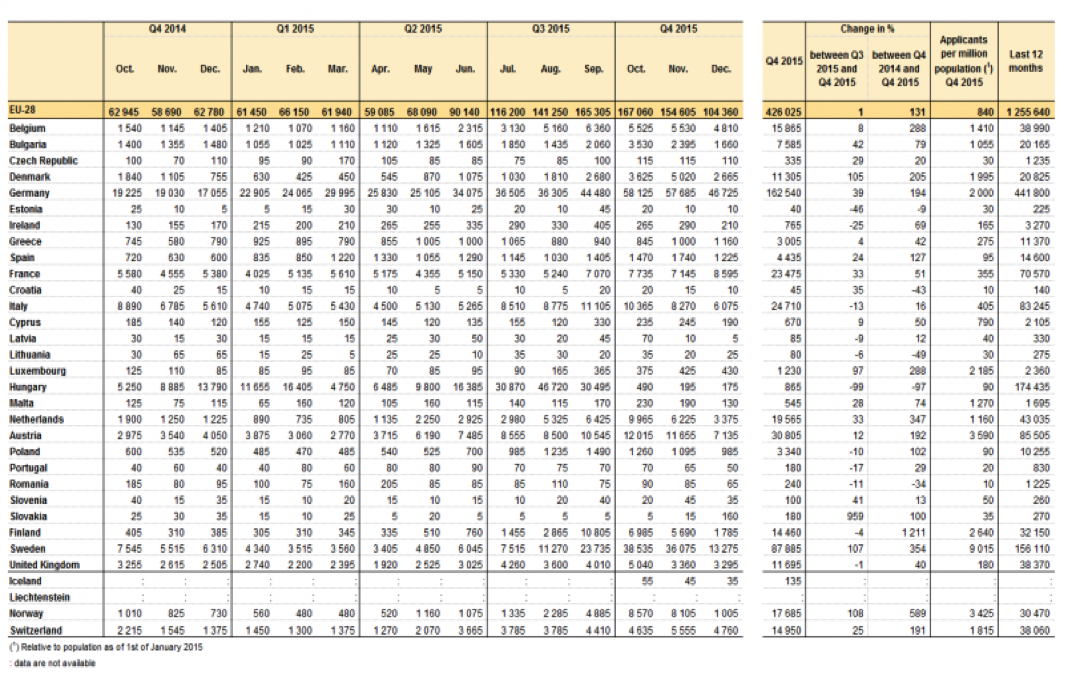

According to EUROSTAT, the EU’s statistical agency, the number of people seeking asylum in the EU in 2015 topped 1.2 million—about twice as many people as applied for asylum in the preceding year. The worsening violence in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan are central in explaining this rise in numbers.

This is the picture of asylum seekers in the EU:

As can be seen, the UK does not receive a substantial proportion of the EU’s asylum seekers. Most other large Member States receive considerably more. Yet, the press and our political leaders are anxious about the numbers of asylum seekers entering the EU. The UK has chosen not to participate in any of the EU’s relocation plans to move asylum seekers from overburdened Greek and Italian islands to other Member States. Instead, the UK government has embarked on a programme of re-settlement of refugees from Turkey and elsewhere in the region, but outside the EU, to the UK directly.

The CEAS is a rather dynamic field of EU legislative activity, but not one in which the UK has chosen to be centrally engaged. The European Commission proposed in April 2016 that the various parts of the CEAS be codified into one single legal framework. This proposal is currently on the table.

The consequences of a UK withdrawal from the EU on the CEAS are not likely to be large for the other 27 Member States, but may be problematic for the UK. At the moment the UK is bound by the first phase measures of the CEAS on minimum reception conditions, the definition of refugee and beneficiary of international protection, and the procedural rules. It participates in the Dublin re-cast rules on responsibility sharing of asylum applications. A UK withdrawal would mean that the UK would need to re-negotiate its participation in the Dublin system if it wants to continue to have the possibility of sending asylum seekers to other Member States to have their asylum applications processed there. At the moment the UK is a substantial net beneficiary of the Dublin system, sending a lot more requests to other Member States to take back asylum seekers than it receives. Though whether the numbers are sufficient to merit the effort is unclear. According to EUROSTAT, the Dublin returns with the UK’s closest neighbour, France are as follows:

| Year | Incoming Dublin requests from France to UK | Requests accepted | Incoming Dublin requests from UK to France | Requests accepted |

| 2011 | 226 | 63 | 289 | 182 |

| 2012 | 226 | 59 | 191 | 71 |

| 2013 | 195 | 46 | 186 | 73 |

| 2014 | 158 | Data not available | 174 | 74 |

A decision to leave the EU would put the UK in a similar position to Denmark—which participates in the Dublin system, but not in any of the other measures of the CEAS. However, the European Commission announced in April 2016 that it would be proposing a new consolidated instrument on asylum bringing all the CEAS measures into one Directive. It has also proposed substantial changes to the system with a view to creating a more regulated and coherent asylum system across the continent. If the UK wants to participate in this new system, it will only be able to do so if it remains in the EU.

[1] Source: UNHCR Statistical Yearbook 2014.

[2]EUROSTAT Asylum Quarterly report 9 December 2015.

[3]EUROSTAT Asylum Quarterly report 9 December 2015.

[4] EUROSTAT Asylum Quarterly report 9 December 2015.