- BY Colin Yeo

A draft submission to the Windrush lessons learned review

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

I’ve been working on a submission to the Windrush lessons learned review. The final date for submission of evidence is 19 October 2018 and I’d urge anyone interested in immigration policy to consider putting in a response, no matter how short. I’ll be sending in this submission, with any amendments, at 12pm on Friday. I’ll post a link on this page to the final version once it is sent. [Update 26 October: here is the final version.]

You can see the terms of reference and the membership of the review’s Independent Advisory Group at the link above.

I am interested in readers’ feedback on this draft. If you have comments or changes you would suggest, do leave a comment at the foot of this post and I’ll carefully consider them. If you’d like to add your name to this submission (you may well disagree with some or all of it, there is no obligation!) there’s a submission form at the bottom to do so. You can also use the submission form to send me your feedback if you’d prefer it not to appear as a public comment. If you’d like to use some of the ideas for your own submission, please do so.

This is a draft version, not the final version.

Submission to Windrush lessons learned review

Page contents

My name is Colin Yeo and I am a barrister specialising in immigration law. I am based at Garden Court Chambers in London, which is the leading set of barristers’ chambers in immigration law. I also founded and edit the Free Movement website (www.freemovement.org.uk) which has since 2007 provided immigration practitioners, policy-makers, journalists and members of the public with commentary and insight on immigration law issues.

I have a particular interest in what is often called the “hostile environment” after an interview given by then Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012. This is officially referred to within the Home Office as the “compliant environment”. As well as representing affected clients I have been writing about the specific laws and policies comprising the hostile environment since they were first announced. I have also published ebooks aimed at fellow immigration lawyers on the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016, the main legislative vehicles for the hostile environment.

Executive summary

- The fundamental cause of the problems experienced by the Windrush generation was the raft of laws and policies known as the “hostile environment.”

- The measures comprising the hostile environment represent a poorly understood revolution in immigration control within the United Kingdom:

- Checks by trained officials at the border have been significantly supplemented by checks within the United Kingdom by citizens on one another.

- Direct internal immigration control enforcement through detection and forced removal has been significantly replaced or supplemented by indirect enforcement through third parties.

- The mix of laws and regulations comprising the hostile environment began seriously in 2006 but were hugely expanded and accelerated from 2012 onwards. The acceleration of this policy brought about a major culture change in the employment market and is now likely to have the same impact in other sectors.

- The effects of the hostile environment have been poorly understood within and outside the Home Office because of combination of an absence of clear policy objectives, an almost absolute absence of research or relevant data collection, a highly defensive and closed culture at the Home Office and a plain failure by civil servants and politicians to understand the lives of those affected by their policies.

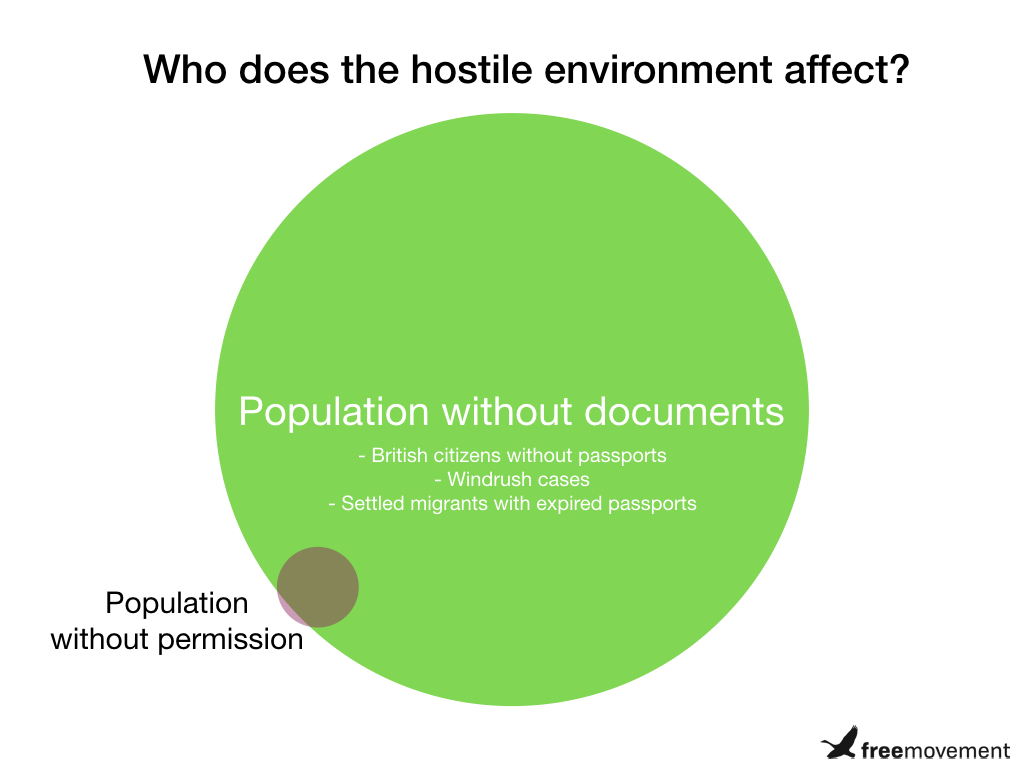

- Policy makers carrying out this revolution have conflated “undocumented” (which includes British citizens without passports, migrants with old documents and lawfully resident migrants without papers) and “illegal”.

- The suffering experienced by the Windrush generation will, until adverse media attention caused a re-think, have been perceived within the Home Office as a sign of policy making success.

- A system of optional and therefore risk based internal citizen-on-citizen immigration checks is inherently racially discriminatory and should be distinguished from a system of compulsory identity checks

Before addressing the specific questions in the call for evidence, I make some general points about the hostile environment and draw attention to an earlier briefing I wrote on the hostile environment from which much of this response is drawn: What is the hostile environment, where does it come from, who does it affect? That was a re-write and refinement of a piece written in May 2017.

The reason for my focus here on the hostile environment is that in my view it is the modern creation and enforcement of the hostile environment that has been the fundamental cause of the problems experienced by the Windrush generation. In particular, the foundational flaw at the heart of the hostile environment policy is the conflation of those without papers (like the Windrush generation) with those without permission.

Development of the hostile environment

The hostile environment represents a revolution in the way in which immigration control is carried out in the United Kingdom. The fundamental change is twofold:

- A move from border checks to internal checks

- A move from checks by officials on citizens to checks by citizens on one another

Historically, immigration control in the United Kingdom was carried out by trained immigration officials at the border. Unlike other European countries, internal identity checks (in the form of either identity cards or a population register) were unknown. The idea of “papers, please” identity checks would have been considered by many to be fundamentally “un-British”.

That historic approach started to change with the introduction of a largely unenforceable and therefore hypothetical duty on employers not to employ migrants without immigration status. This obligation, introduced by the Asylum and Immigration Act 1996, was made more concrete and enforceable with a system of civil penalties introduced by the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006.

Active enforcement of employer penalties was initially limited but increased over time. The maximum fine was doubled to £20,000 in 2014. This has gradually changed the culture in the employment market, leading most employers to believe they were under a duty to carry out immigration checks (which is not in fact the case as a matter of law; see below).

It seems likely that the imposition of civil penalties on employers who employed people without permission caused significant problems for a small group of people, some of whom were part of the Windrush generation. I am aware of some media reports of problems and one reported tribunal case: Baker v Abellio London Ltd [2017] UKEAT 0250_16_0510. Judging whether the problem was “real” or “significant” by the frequency of media reports is unwise because there was very little media interest in such issues until relatively recently. Most of those affected will have felt themselves powerless, suffered in silence and tried to find alternative employment with an employer who was more understanding of their situation and less stringent in applying checks.

The system of outsourcing immigration checks was hugely expanded from 2012 onwards with a new equivalent obligation on landlords and duties imposed on banks introduced by the Immigration Act 2014 and a range of regulatory changes introduced by statutory instrument. This expansion was carried out with no clear policy objectives, no known research into the effects of the existing policy on the employment market and almost no research into the likely impact of the proposed changes.

Inherent discrimination

Every time you encounter a hostile environment check — from an employer, landlord, bank, doctor or school — you are being asked whether you can prove a right to live in the UK. If you are white, middle class, middle aged, take holidays abroad, own your home and have long term employment, you are immune to the effects of the hostile environment. You will rarely be checked and if you are then you possess a passport and you feel secure in your status and your societal role. It will be hard for you to understand the demeaning, emotional and racialised nature of these checks.

One defence of the hostile environment measures is to argue that similar checks already exist in other countries. This misunderstands the nature of the checks introduced in the UK and the checks that take place in other countries.

Many countries have a system of identity cards. It is common for employers, landlords or others to be under a duty to check and record a person’s identity using these cards. Failure to do so may carry penalties. The duty is universal and therefore arguably non-discriminatory.

It is widely supposed that in the UK employers and landlords are under a similar legal “duty” to carry out similar universal and therefore non discriminatory immigration checks on all employees and tenants. This is inaccurate; the actual system in place is instead to fine or prosecute an employer or landlord only if they employ or rent to a person without permission.

If an employer gives a job to a person with permission without checking that person’s papers there is no breach of the 2006 Act. If a landlord rents to a person with permission without checking their papers there is no breach of the 2014 Act. However, employers and landlords are incentivised to carry out immigration status checks because doing so equips them with a defence to the imposition of a large fine if they do inadvertently employ or rent to a person without permission.

This approach of incentivising but not legally obliging encourages, or at least allows for, a “risk based” approach by employers and landlords, which risks encouraging racial discrimination. A white person with a local accent may well be regarded as low risk and employable without checks. A black person or a person with a foreign name or an accent may be regarded as high risk and therefore unemployable without checks.

The problem here is that the UK system is based on inherently discriminatory immigration checks not universal identity checks because the penalties are based on the immigration status of the employee or tenant.

Those defending the system might say that race discrimination and equality legislation, such as the employer and landlord codes introduced by the Home Office, exists to deal with any discrimination. This response merely recognises that the policy causes an increased risk of discrimination and also fails to consider how the equality legislation might be enforced in practice. A person who fails to get a job for lack of papers, or who is asked for papers and suspects they may not have been asked but for the colour of their skin, is hardly able to bring a legal case or complaint on that basis.

The only piece of research commissioned by the Home Office into the impact of the hostile environment was into the right to rent pilot. Others can comment better on the design of that research. The conclusion was that the pilot did not lead to discriminatory outcomes for affected tenants. However, the same research also showed that BME tenants were more likely to be asked for proof of their immigration status and that some landlords made discriminatory comments.

Whether ministers read the research in sufficient detail or had these aspects of the research reported to them by civil servants is unknown. But it is clear that the right to rent policy was implemented despite Home Office research showing that some people would be asked to prove their immigration status because of the colour of their skin.

Who is most likely to experience hostile environment checks?

There are two ways in which a person can be affected by the hostile environment:

- Firstly, some citizens and residents are more likely to experience hostile environment checks than others.

- Secondly, some of those who are checked are more likely to struggle to prove their right to reside than others.

As already discussed, a white, middle-aged, middle-class, home-owning, foreign-holiday-taking and long-term-employed person has little if any contact with the hostile environment and little if any appreciation of the impact of being asked to prove his or her right to live in the country. Most ministers and civil servants would match most or all of these characteristics.

It is a person who possesses one or more of the following characteristics who is most likely to be challenged for their papers by their fellow citizens:

- Move frequently between jobs

- Rent accommodation

- Black or ethnic minority appearance

- “Foreign” name

- “Foreign” accent

Young people and black and ethnic minority people are therefore more likely to face hostile environment checks than other citizens.

For some of those who experience the checks, it is no more than a minor inconvenience. If the person concerned is a British citizen and already possesses a passport to prove it, he or she will simply be able to produce the passport.

Who comprises the undocumented population?

There are two main groups of the undocumented population:

- British citizens without passports

- Lawful migrants without papers

Some within these two groups may find it relatively easy to obtain documents if needed but some will struggle.

British citizens

There are estimated to be 9.5 million ordinary residents of England and Wales who do not possess a passport. Many will be British citizens. Some will be young, others will be old. Some will never have applied for one because they did not think they needed it.

Some British citizens may now find they are forced to apply for a passport not in order to take a holiday abroad but to live within their own country. A British passport is now needed by British citizens to get a job, rent accommodation, get medical treatment, open a bank account and more. Identity cards were abolished in 2010 but measures since then have introduced a de facto identity card system by the back door – but without any of the convenience or universality of an actual identity card system.

Some British citizens will struggle to prove their entitlement to a British passport. This is particularly true of the children of the Windrush generation and of EU citizens. Both the Windrush generation and EU citizens may well have acquired lawful, permanent residence in the UK by automatic operation of law (the Immigration Act 1971 and EU Directive 2004/38) but without documentary proof being generated. A child of a permanent resident is automatically born British under the British Nationality Act 1981. But some children born entitled to British citizenship in this way may have serious difficulties proving it because there may be no simple documentary proof of their parent’s status at the time of their birth.

I am concerned that this is going to a significant problem in future years, as described in this research paper I wrote for the Eurochildren project at the University of Birmingham: The impact of the UK-EU agreement on citizenship rights for EU families, Eurochildren Research Brief, no. 2.

Lawful migrants

There are an unknown number of migrants to the UK who have never acquired British citizenship but who are lawfully resident. The Windrush generation is included in this group, but the group is potentially much larger.

In legal terms the Windrush generation can broadly be defined as those Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (the status of “British citizen” did not exist until the British Nationality Act 1981) who moved to and lived in the UK lawfully before commencement of the Immigration Act 1971 and who retained their lawful residence by operation of law afterwards. They were not required to apply for proof of their status at the time and were not automatically issued with papers to prove their status.

For many years this was not necessarily a problem. Employer checks from 2006 onwards caused growing issues, particularly after the employer fines were increased, and travel abroad risked refusal of re-entry. However, it was the expansion of hostile environment checks and the culture change associated with that which caused serious suffering for this group.

There are other long term resident migrants in possession of Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR) who may struggle to prove their status. For example, their ILR stamp may be in an old and expired passport. Obtaining a new passport from their country of nationality may be no simple matter and an application to the Home Office for a replacement stamp is currently charged at £229 per person.

For example, under the new NHS charging regulations, a long term resident with old papers will now need to obtain a new passport and a new ILR stamp in order to access potentially life saving treatment.

Children form another group and are at particular risk of being lawful but losing their lawful status because of either an omission on the part of their parents or because of prohibitively high Home Office application fees pricing out their parents.

The other group of migrants with lawful status but not necessarily documentary proof are EU citizens. At present, it is (hopefully) universally understood that possession of an EU passport carries with it permission to live and work and rent property in the UK. That understanding is highly likely to break down after Brexit irrespective of what the law actually is. Further, the “settled status” scheme does not include the issuing of physical proof of status to those who apply for it and obtain it. Instead the Home Office expects employers and landlords to phone a hotline or conduct a computer check. It seems likely that some employers and landlords will not understand this system or will simply decide it is too inconvenient. The effect would be discrimination against EU citizens.

Further problems are likely to arise for EU citizens once a distinction must be drawn by employers, landlords and others between resident EU citizens with a pre-Brexit right to work and rent and new post-Brexit arrivals from the EU who will not have such rights. In the absence of physical proof of status, there will be no way for an employer or landlord easily to determine whether a particular EU citizen falls into the first group or the second.

Specific questions

What, in your view, were the main legislative, policy and operational decisions which led to members of the Windrush generation becoming entangled in measures designed for illegal immigrants?

The conflation by policy makers of the undocumented population with the unlawfully resident population and the introduction of a raft of policies targeting the undocumented population is the fundamental cause of the problems experienced by the Windrush generation. This was compounded by the rapid expansion of hostile environment measures from 2012 onwards, with no research on the existing impacts and very limited and somewhat questionable research on the likely future impacts.

There was no recognition of the problems faced by undocumented but lawfully resident individuals until far too late in the day, and then only in response to media and public opinion pressure. The basic problem is

- Some lawful residents of the UK do not possess immigration status papers

- Further, that some of that group would struggle to obtain them.

Even now, the official approach is essentially that where a person lacks documents, that is their problem and for them to resolve. A very limited exception to that principle has been made for the Windrush generation and is, perhaps, also to be applied to EU citizens under the settled status scheme. This begs the question of why a similarly helpful and proactive approach cannot be adopted in other cases.

What other factors played a part?

- Lack of awareness of the complexity of the legacy of the Immigration Act 1971 was one important contributing factor to the specific issues experienced by the Windrush generation.

- The standard of proof to establish long residence in the UK was clearly being set at an unrealistic level by Home Office officials. I personally acted in one case where an absurd refusal by the Home Office was easily overturned on appeal, although only after considerable stress, inconvenience and cost to the person concerned.

- Officials of all levels take their cues from ministers. The ministerial message at the Home Office since 2010 is that immigration is too high and must be reduced. Officials are well aware of pressure on the department to meet the net migration target and the political cost to ministers of failing to do so. The net migration target, consistently negative comments on migrants and immigration and constant linkage, to the point it seems to be subconscious now, between immigration, crime and terrorism, have all contributed. This has embedded a culture of refusal across all case working teams at the Home Office.

Why were these issues not identified sooner?

- Immigration policy since 2010 has, in general, been hostile to immigration and therefore to migrants. Numerous measures have been introduced which, intentionally, strongly adversely affect migrants and their families. These policies disproportionately affect ethnic minorities. Ministers and civil servants are therefore aware that immigration policy causes significant suffering to the BME population; indeed, it is supposed to. To a significant extent, therefore, the suffering experienced by the Windrush generation was probably perceived within the Home Office as a sign of policy making success. People without documents were forced to apply for documents, forced to pay significant fees to do so, the applications were judged against an exceedingly high evidential standard and those people’s lives were made intolerable in the event of failure. This will have looked like success, not failure, within the Home Office. It was only when sustained media attention shone a light on the situation and public opinion was revealed to be sympathetic that this was re-evaluated.

- The Home Office is afflicted by an aggressively defensive culture that has been likened to the famous Millwall chant of “No one likes us, we don’t care.” This hostility to critics has blinded civil servants and ministers to legitimate criticism and to genuine problems with the immigration system that they are responsible for creating.

- Ministers and civil servants are remote from the people whose lives are profoundly affected by the immigration system. There is little or no informal or formal feedback mechanism enabling ministers or civil servants to become aware of unintended consequences.

- The high turnover of Immigration Ministers (six in eight years since 2010) means that there is little opportunity for the minister to learn their brief, question the information they are provided with by civil servants or appreciate trends or themes in media stories on immigration.

- There is no stakeholder group organised by the Home Office for long term residents or dealing with “ordinary” in-country immigration case work, as far as I am aware.

- Senior Home Office civil servants appear to be averse to independent scrutiny of decision making. For example, rights of appeal against immigration decisions to an independent judge have been heavily curtailed since 2014 and replaced with an internal “administrative review” process that is far more limited in scope and has a far lower success rate.

- Neither Home Office ministers nor civil servants appear to be genuinely interested in equality impact assessments nor in data on equality impact. The impact assessments for the various hostile environment measures in the Immigration Acts 2014 2016 were very poor indeed.

- Inspection reports by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration appear to be treated dismissively by ministers and civil servants. Rather than prioritising actionable improvements suggested by and agreed with the Chief Inspector, such improvements remain un-implemented for years. The Chief Inspector himself has complained that close to half of his recommendations since taking office in May 2015 have not implemented (4% rejected and “over 40%” accepted but not acted upon). The decision tightly to control the publication of the reports and to publish multiple reports at one time also intentionally reduces media scrutiny of the reports. Political expediency and short term media management trump transparency and scrutiny.

What lessons can the Home Office learn to make sure it does things differently in future?

- Not to conflate undocumented with illegal. This sounds simple but has profound and wide ranging implications for the treatment of EU citizens after Brexit.

- To research the effect of existing policies before radically extending those policies and to research the likely impact of the extension of those policies.

- That scrutiny and criticism can help improve policy and implementation.

Are corrective measures now in place? If so, please give an assessment of their initial impact.

The corrective measures put in place specifically for the Windrush generation appear to be effective. In the absence of research or data on how many Windrush generation migrants have not come forward and who remain undocumented, it is hard to judge how successful the measures have been.

There is no public acknowledgement by the Home Office that the problems experienced by the Windrush generation are experienced more widely by other lawful residents who do not possess proof of their status. The high fee for replacement ILR/NTL stamps is a serious issue.

Further, the settled status scheme for EU citizens seems designed to cause Windrush-style problems for EU citizens in future:

- First of all, an unknown number of EU citizens will not have acquired settled status by the time of the deadline. There is little public acknowledgement of this fact by government, no information on how they will be treated and no attempt to estimate the number of people affected.

- Secondly, EU citizens who do apply for and obtain settled status will be denied any physical proof of their status to show to employers, landlords or public services, or to distinguish themselves from EU citizens arriving without full residence rights after Brexit or after the end of any transition period.

What (if any) further recommendations do you have for the future?

The system of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks on which the hostile environment policy relies is a disaster for community relations in the United Kingdom and encourages racial discrimination.

In particular, the system of imposing no duty on employers and landlords to check immigration status but imposing a penalty for employing or renting to a person without permission encourages employers and landlords to follow a risk based and therefore discriminatory approach.

After Brexit, it is likely that the shift in immigration control from border controls to internal controls will accelerate. Under current plans, EU citizens entering the UK in future will not require a visa but will not have an automatic right to work. They will therefore be able to freely enter the UK and internal controls will be required in order to enforce any prohibition on working.

The high level policy options include:

- Maintain the status quo and accept some additional racial discrimination in the employment and rental markets as an inevitable consequence, as well as inconvenience and additional expense to lawful residents of the United Kingdom, including citizens, who lack valid immigration documents.

- Impose an actual duty on employers and landlords to carry out immigration checks, scrap the existing penalties and replace them with penalties for failing to conduct the checks no matter what the immigration status or ethnicity of the person concerned.

- Introduce an identity card system and replace the current inherently discriminatory immigration-based checks and penalties with identity-based checks and penalties.

I would respectfully suggest the first of these options is unacceptable, particularly in the context of Brexit and the creation of a very large new population of residents with lawful residence but without documentary proof of that lawful residence.

SHARE

2 Responses

This is an excellent sumbission. One suggestion: I wonder if it would be worth adding something on the Home Office’s handling of appeals. In a number of Windrush cases (such as the one you mention) and other egregious refusals that get press attention, the cases have proved easily winnable on appeal, because the Home Office’s decision-making has not been in line with the law, and/or the Home Office’s requests for evidence have been ridiculous. Practitioners often know their appeals are very likely to succeed, and the Home Office also knows, or should know, this. Yet it has so far – as far as I know – been very rare for the Home Office to withdraw appeled decisions before the cases are heard. This will generally create a delay of many months during which the appellant remains stripped of rights. This has – surely deliberately – exacerbated the sort of suffering to which you refer.

Dear Colin, your submission makes some great points. I am not a legal expert but have worked with asylum seekers and refugees for several years.

I also write as a “second generation migrant” whose grandfather came to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950’s, followed by his wife and children four years later. Whilst I have not been directly affected by the Windrush scandal, I did feel the uncertainty of wondering what might happen if my status was challenged.

When Sajid Javid made his speech as new Home Secretary, he seemed pleased to announce that under his watch the “hostile environment” was out and the “compliant environment” is in! This new term still implies power to the Home Office and acquiescence – a quiet submissiveness – on the part of those applying for/claiming leave to remain. In my view, for the Home Office to prevent this/or similar happening again there must be a change of attitude, the way policy is implemented and an understanding of how that policy impacts lives.