- BY Nick Nason

Blocking deportation: seven tips for an appeal-proof tribunal judgment

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

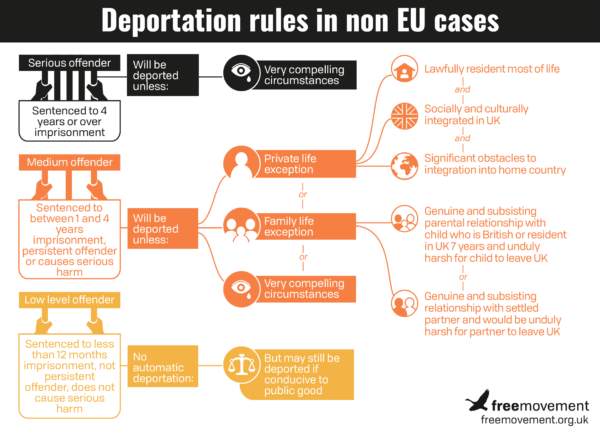

The judgment in SSHD v SS (Jamaica) [2018] EWCA Civ 2817 continues a trend in which ‘foreign criminals’ who had been successful in their initial tribunal appeals against deportation have had those decisions overturned in the Court of Appeal.

Free Movement has covered cases like this multiples times in recent years (I can count at least half a dozen posts following this pattern in the last 18 months alone), most recently by Nick Webb in his write up of MR (Pakistan) [2018] EWCA Civ 1598. In this post we will tentatively suggest some ways in which tribunal judges might make more sustainable decisions in this area.

Bullet-proofing required

Although sloppy decisions in any area of law are likely to be vulnerable to onward appeal, perhaps nowhere is this truer than in deportation litigation.

If the Home Office loses in the First-tier Tribunal, the written decision will be pushed under the noses of as many judges as possible before it gets to the point where the reversal can no longer be routinely appealed (usually the Court of Appeal).

Tribunal judges who find that an appellant has, to paraphrase Lord Justice Laws in SS (Nigeria), a “very strong claim indeed” to displace the public interest in deportation face a formidable challenge in justifying that stance. They will need to distil a complex web of statutory provisions and Immigration Rules into their determinations, guided by an unwieldy stack of (sometimes) competing authorities.

That was not, it appears, what happened in SS (Jamaica).

The determination in SS (Jamaica)

SS got just shy of 3 ½ years for possession with intent to supply Class A drugs. No information is given on his age, but he had been in the UK for over 20 years bar one six-month period abroad in 2006-2007. It doesn’t appear that he had any previous history of offending.

SS had parental relationships with five British children including a nephew who he raised as his own. A government social worker assessed that the best interests of at least two of them would be served by his remaining in the UK. The First-tier Tribunal allowed the appeal against deportation and the Secretary of State’s appeal to the Upper Tribunal was dismissed.

Without seeing the First-tier Tribunal determination in full – only the bits to which the Court of Appeal has decided to refer – it can be difficult to analyse whether or not an appellant’s case could have been saved by a better written judgment. However, according to Simon LJ, giving judgment, the tribunal in SS (Jamaica) made the following errors:

There was no reference to a crucial step in the necessary analysis of the position outside the Rules: namely, whether there were circumstances which were sufficiently compelling (and therefore exceptional) to outweigh the public interest in deportation, see MF (Nigeria) at [46]. To the contrary, the FtT’s findings were that ‘the public interest did not require the deportation of the [Respondent]’ (§62); and the Judge’s conclusion was that, having balanced the factors that weighed on each side, that ‘deportation is neither appropriate or necessary’ (see §78), [emphasis added]. The Judge’s approach fatally undermined her conclusion.

Any determination which states, in pretty much direct contradiction to section 117C(1) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (as amended) that “the public interest [does] not require the deportation” of the foreign criminal, is off to a bad start. (Section 117C(1), for the uninitiated, reads “the deportation of foreign criminals is in the public interest”.)

What could the tribunal judge have done differently?

The Magnificent Seven

Recent examples of robust determinations can be found in SSHD v Garzon [2018] EWCA Civ 1225 and in SSHD v Barry[2018] EWCA Civ 790, which survived repeated challenges by the Secretary of State from the First-tier Tribunal all the way up to the Court of Appeal.

Following a non-scientific non-exhaustive review of these and other authorities, we suggest that sustainable determinations in this area are more likely to include the following:

- A description of the public interest in deportation (in detail). Great weight must be attached to it (whether you think this is right or wrong). This is because:

- The source of the policy is primary legislation; and

- The nature of the policy itself (moral dimension, condemnation of serious wrongdoing, protection of the public)

- Reference to the three component factors which comprise the public interest to avoid any suggestion that its weight has not been fully appreciated. As a reminder, these are

- Preventing reoffending;

- Deterring other would-be criminals; and

- Expressing public revulsion (or lack of confidence in the immigration system, as preferred by Lord Wilson in Hesham Ali)

- Specific reference in the determination that “very compelling reasons” will need to be shown (if an appellant does not fall within a statutory exception) to resist deportation. Perhaps observe that “very” indicates a very high threshold and that the word “compelling” means circumstances which have a powerful, irresistible, and convincing effect.

- A balance sheet approach, listing the pro and cons on each side of the argument as suggested in Hesham Ali at paragraphs 83 and 84, identifying each and every relevant circumstance, both for and against deportation.

- Lots of detail. The only two recent appeals (that we have seen) in which individuals were successful in challenging decisions to deport and then survived the Court of Appeal (Barry and Garzon) ran to 169 paragraphs and at least 125 paragraphs, respectively.

- Evidence that the judge has at all times borne in mind the seriousness of the appellant’s criminal behaviour, preferably by making constant reference to it throughout the determination.

- An embrace of – not just a nod of the head to – Laws LJ’s dicta in SS (Nigeria) that the public interest in deportation can only be outweighed “by a very strong claim indeed”, preferably with specific reference to this in the determination

Of course, this is not a box-ticking exercise. Mere formulaic reference to the themes in this list won’t mean that a determination is beyond reproach. But if a judge has touched on (and can be seen to have bought into) all of the points above, scope for challenge narrows significantly.

Looking at the facts in Barry (which succeeded), they are not strikingly different from those in the present case. One wonders what might have been had the approach suggested above had been followed.

SHARE