- BY Ruth Mercer

143-day average waiting times for detained asylum seekers – another unlawful system?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

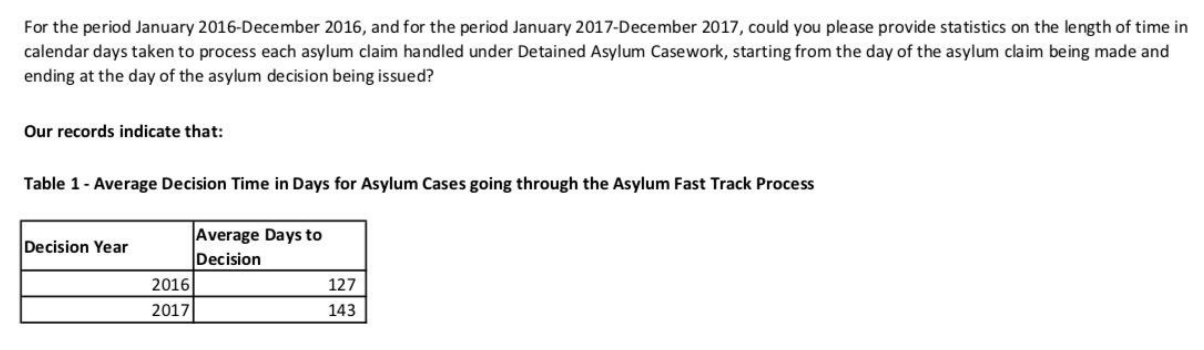

New figures from the Home Office reveal that asylum seekers are being held in detention centres for five times longer than the government’s own recommendation when the system was introduced. The data, obtained from a Freedom of Information request, shows that the average asylum applicant under Detained Asylum Casework is being detained for 143 days, in stark contrast to the previously advertised 28-day target. It’s an embarrassment for the Home Office, raising questions about the legality of an asylum system which was only introduced because its predecessor had been declared unlawful.

Until 2015, the Home Office considered the cases of asylum seekers held in detention under the Detained Fast Track policy, under which asylum applicants were allowed only one day to prepare for interview and six days to prepare any appeal. The Detained Fast Track was abolished after numerous legal challenges brought by the charity Detention Action. The Court of Appeal (in Lord Chancellor v Detention Action [2015] EWCA Civ 840) ruled that the speed of processing was inherently unfair.

A few weeks later the Home Office introduced the current system, known as Detained Asylum Casework (DAC). Its criteria for detaining asylum seekers hinges on whether there is a reasonable likelihood of deportation and whether applicants pose a risk of absconding. Under the initial Detention: Interim Instruction DAC policy guidance, asylum cases were to be decided by the Home Office within 28 days.

Those guidelines have since been replaced by a series of documents which provide no specific deadline for decision-making, although many DAC practitioners complain that cases are being considered far too slowly by the Home Office. The average time to a decision in 2017, at 143 days, represents a 13% rise on the previous year.

The new figures form part of research adding weight to a growing opinion that DAC may now be considered unlawful. Although the Home Office has a statutory right to detain for immigration purposes, its powers are tempered by the Hardial Singh principles summarised in Lumba v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] UKSC 12:

- The Secretary of State must intend to deport the person and can only use the power to detain for that purpose;

- The deportee may only be detained for a period that is reasonable in all the circumstances;

- If, before the expiry of the reasonable period, it becomes apparent that the Secretary of State will not be able to effect deportation within a reasonable period, he should not seek to exercise the power of detention;

- The Secretary of State should act with reasonable diligence and expedition to effect removal.

With an average waiting time of 143 days for an asylum claim to be decided, it may be argued that DAC contravenes the second, third and fourth limbs of the Hardial Singh principles. These delays are not reasonable in the circumstances, particularly as they are so much longer than the time period envisaged in the interim instructions. The Secretary of State cannot expect to effect deportation in a reasonable time for DAC cases when the data shows that the average case takes five months for a decision to be made. The delays can also be considered in breach of the requirement to act “with reasonable diligence and expedition”.

In finding that the Detained Fast Track was unlawful in 2015, the Court of Appeal in Detention Action provided specific criteria for assessing the lawfulness of a detained asylum system overall. It ruled that any new system must be judged on “a full run of cases” and that an assessment should be made as to whether inherent unfairness could be found “in the system itself”. In disclosing an average wait of 143 days (meaning that some delays must be even worse), the new figures do indeed cover a breadth of cases and therefore suggest inherent unfairness in the DAC system.

[ebook 17797]It will be interesting to see how DAC develops following the government’s recent consultations with the Tribunal Procedure Committee to consider a return to accelerated timescales for detained asylum appeals. It is perhaps ironic that the Home Office is seeking to reduce timescales for the processing of DAC appeals when its own management of initial claims is so slow. It has already been established in Detention Action that a return to rapid and inflexible appeal timescales would be unfair, and this would not assist the issue of unnecessary Home Office delays in making initial decisions.

Just as the Detained Fast Track was too fast, denying claimants a right to a fair hearing, so now the DAC system may be too slow, resulting in claimants being detained far longer than is fair or lawful. Serious changes are needed in the DAC policy, to ensure that when it becomes apparent that an applicant will not removed within a reasonable period they are promptly released and not subjected to unlawful detention.

A full research paper with findings and recommendations on this subject, written by Ruth Mercer of Westminster University and Barnes Harrild and Dyer Solicitors and supervised by Sandi Kudhail of Westminster University and Asylum Aid, is available to download here. Thank you to all the practitioners who gave their time to be interviewed.