- BY John Vassiliou

Briefing: Hong Kong and British National (Overseas) status

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

In this briefing we look at the British National (Overseas) citizenship status held by an estimated 2.9 million people in Hong Kong.

Before we begin, a quick reminder that there are six different types of British nationality:

- British citizenship

- British Overseas Territories citizenship

- British Overseas Citizenship

- British Subject status

- British National (Overseas) status

- British Protected Person status

Of the above, the most common is British citizenship. The other statuses are remnants of Empire and are becoming increasingly obscure. British National (Overseas) status would normally count as obscure but has been in the news on and off since 2019 because of the protests in Hong Kong and escalating retaliation by China, so we thought we would put out an explainer.

Due to its unwieldy title, you will often see the type of British nationality we are looking at written as British National Overseas status, BN(O) or just BNO.

Some quick background on Hong Kong

Hong Kong is on the southeast coast of China. It is made up of three main areas: Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories.

Hong Kong first came under British imperial control when Britain invaded in 1841 to utilise its strategic location for military purposes. Hong Kong Island became a colony in 1842 after the First Opium War. Kowloon was acquired after the Second Opium War in 1860. Finally, the New Territories were acquired in 1898 through a lease agreement between Britain and China, allowing full British control over the increasingly influential region for a finite period of 99 years.

Those 99 years came to an end in 1997, when formal control over the entire Hong Kong region was returned to China.

Nationality status of Hong Kong citizens

Hong Kong is now one of China’s Special Administrative Regions. Since the 1997 handover, residents have been entitled to their own “HKSAR” passport. Prior to handover, the majority of Hong Kong residents would have been classed as British Dependent Territories citizens with a right of abode in Hong Kong only (not the UK). In the ten years leading up to handover, they were entitled to apply to register for BNO status.

Many did, either to retain their connection to the UK, or simply because this was their only way to obtain a passport at that time. BNO status was created on 1 July 1987 by the Hong Kong Act 1985 and the Hong Kong (British Nationality) Order 1986 as part of the handover preparations.

Acquisition of BNO status

BNO status was an entitlement, but had to be acquired by registration. Acquisition was not automatic. The final deadline for registration for most people was 1 July 1997, though for some it was extended to 31 December 1997.

BNO status thus belongs only to a closed, and naturally declining, group of people. Anyone who missed the deadline for registration cannot retrospectively apply for this type of nationality status, even if they would have been eligible at the time.

To qualify for BNO status, a person had to be a British Dependent Territories citizen by connection with Hong Kong. Those who did not register for BNO status and had no other nationality or citizenship on 30 June 1997 automatically became British Overseas Citizens on 1 July 1997.

How many people have BNO status?

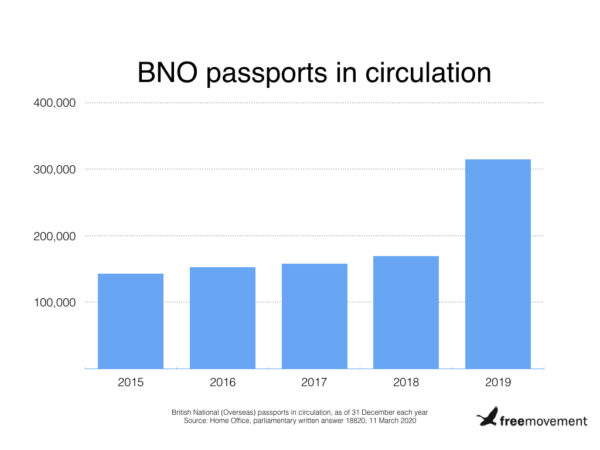

The estimated number of people who hold BNO status — 2.9 million — is almost ten times higher than the number of BNO passports issued. In December 2015, there were only 143,000 valid BNO passports in circulation. This has more than doubled to 350,000, mostly over the course of 2019. I’m sure we can all guess why.

As we regularly point out on this blog, a passport does not confer a citizenship status; a passport is merely a travel document. The comparatively small number of BNO passports in circulation is likely to be a simple reflection of just how useless a status it is (for other useless British nationality statuses, check out British Overseas Citizenship).

Rights associated with BNO status

A BNO is a Commonwealth citizen, has the right to hold a British passport, and has the right to seek consular assistance and protection from UK diplomatic posts. As the Foreign Office is regularly at pains to point out, though, there is no legal right to consular assistance because consular assistance is provided at its discretion.

The right to ask for consular assistance is a particularly hollow one for BNOs because consular assistance is not provided to BNOs in the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, and Macao. That is because the People’s Republic of China does not recognise dual nationality and all ethnically Chinese people are considered to be Chinese nationals only. So consular assistance is of no use whatsoever to BNO citizens caught up in the protests and worried about extradition to mainland China.

[ebook 57266]Crucially, BNO status does not include the right of abode. Holders therefore do not have any automatic right to live or work in the UK and are subject to immigration controls just like all other non-EEA nationals.

For the purposes of European Union law, BNOs are not considered to be British citizens and thus cannot avail themselves of free movement rights. The words “European Union” have never appeared on the front cover of BNO passports (unlike British citizen passports, which only stopped using those words on 30 March 2019).

For visit purposes, BNOs are considered to be non-visa nationals, meaning that they can visit the UK without applying for a visa in advance. But if you are a BNO hoping to visit the UK and take advantage of the fancy new e-gate admission system, think again. In April 2019, the Home Office confirmed to Stuart McDonald MP that e-gates were not an option for BNOs, who must instead convince an immigration officer that they are a genuine visitor. So far as we can establish, this position has not been changed since then.

One small advantage for a BNO is that, if they do get a UK visa under the normal immigration routes for non-EU citizens and eventually get indefinite leave to remain, they are entitled to register as a British citizen one year later (subject to the usual residence requirements). This is slightly cheaper than naturalisation, and removes the element of discretion that naturalisation applicants must face.

Why no right to live in the UK?

The right of abode is a fundamental aspect of citizenship statuses around the world. It’s therefore fair to ask: if BNO status does not confer the right of abode in the UK, what was the point of it?

In the run-up to the handover there certainly were calls for Hongkongers to get full British citizenship with the right of abode, including from Hong Kong Governor Chris Patten. These calls were not heeded for (as I understand it) two reasons.

Firstly and perhaps obviously, the UK government feared the potential for a sudden influx of over three million new British citizens and was worried about the difficulties of “absorbing” that many new arrivals into society.

Secondly, it was argued that to extend full citizenship would threaten Hong Kong’s stability and prosperity, thus contravening the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong. The offer of a mere 50,000 grants of full British citizenship at the time of handover was enough to cause a stir with China.

BNO status is only one example of the UK massively letting down former citizens of its colonies. Other examples include Windrush generation Commonwealth citizens being stripped of the right of abode by the Commonwealth Immigrants Acts; Malaysian British Overseas Citizens; and the Chagos Islanders. I became aware when researching this article that BNO status had come to be known as “Britain Says No” in reference to Britain saying no to full citizenship with right of abode for Hong Kong citizens.

But more recent developments suggest that securing BNO status might now pay off.

Residence rights in future

In May 2020, China announced a significant new security law for Hong Kong which would increase Beijing’s control over the supposedly autonomous region. In response, the Home Office announced:

if China follows through with its new national security law, the UK government will explore options to allow BN(O)s to apply for leave to stay in the UK, if eligible, for an extendable period of 12 months. Hong Kong BN(O)s currently have the right to enter the UK for six months.

The UK government has made this move as the new security law will undermine the existing legal commitments to protect the rights of Hong Kong people.

When the security law came into effect in June 2020, the UK government confirmed and even extended this visa offer. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab told Parliament on 1 July:

We will grant BNOs five years’ limited leave to remain, with a right to work or study. After these five years, they will be able to apply for settled status, and after a further 12 months with settled status, they will be able to apply for citizenship. This is a special, bespoke set of arrangements developed for the unique circumstances we face and in the light of our historic commitment to the people of Hong Kong

Raab also confirmed that “all those with BNO status will be eligible”, not just those who currently hold BNO passports. Full details are to follow from the Home Office.

This is good news for BNOs who want to emigrate, although it may exclude the less well-off. This isn’t an offer of asylum or the right of abode: it is a visa, and visas are expensive. BNOs would presumably be liable for the Immigration Health Surcharge, soon to be £624 per year with a reduced rate for children. Over five years, that would be £3,120 per adult applicant plus the visa fee itself (the relatively affordable UK Ancestry visa, also granted for five years at a time, is £516). So the upfront cost for a single adult might be around £3,600, eventually followed by the cost of indefinite leave to remain (£2,400) and registration as a citizen (£1,200).

Instead, the government could and should legislate to confer the right of abode on all BNOs. This would have the added benefit of not burdening an already creaking Home Office with a potential 2.9 million visa applications.

This article was originally published in September 2019 and has been updated to take account of developments since then. For more on the proposed BNO visa, see UK visas and citizenship for Hongkongers: what has been announced?.

5 Responses

There is also the important aspect that BNO status was a bit of a trick by the UK Government; and it was thanks to persons such as Lord Avebury, that some concessions were made for ethnic minorities in HK.

The most fortunate were those that did not register for the BNO and retained only BDTC status; they were, for all purposes, stateless. Family of former Gurkhas, as well as those in the Indian and Pakistani community were widely affected.

We still regularly assist BNO holders here in HK with BNA81 4B applications; unfortunately the ethnic Chinese holders cannot avail themselves of this for the reasons stated in your article.