- BY Colin Yeo

Briefing: what is the hostile environment, where does it come from, who does it affect?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

- What is the hostile environment?

- What is the purpose of the hostile environment?

- What are the origins of the hostile environment?

- The modern hostile environment: the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016

- The hostile environment, public services and civil society

- What has been the impact of the hostile environment?

- What would it take to undo the hostile environment?

Theresa May declared in an interview with the Telegraph in May 2012 that she wanted to create a “really hostile environment” for irregular migrants in the UK. In this blog post we look at the evolution of the hostile environment, consider what measures fall within the overarching policy and examine the effects on individuals.

We refer here to the policy as the “hostile environment” because that was the label originally applied to the set of policies by its architect, the Home Secretary, in that 2012 interview. Beginning in 2017, the Home Office started to refer to the set of policies as the “compliant environment” but this represents a change of label rather than a change of product.

The hostile environment includes measures to limit access to work, housing, health care, bank accounts and more. It is characterised by a system of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks. The majority of these proposals became law via the Immigration Act 2014, and have since been tightened or expanded under the Immigration Act 2016.

It is not that illegal entry or overstaying were not previously criminal offences. Under the Immigration Act 1971 being knowingly unlawfully present in the UK or breaching the conditions of a visa are criminal offences. Convictions have steeply declined since a peak in 2005, however, and prosecutions have levelled out at around 500-600 a year. It seems the Home Office and/or police have neither the resources nor the will to enforce existing immigration laws. Similarly, the number of enforced removals of immigration offenders has fallen in recent years.

On the face of it, therefore, the hostile environment criminalises behaviour that is already criminal. It does go further, though, by also criminalising and penalising private individuals and entities who fail to enforce immigration laws in their dealings with members of the public.

What is the hostile environment?

There are plenty of aspects of current immigration policy which are unpleasant and “hostile” to immigration or migrants in a general sense, including the astronomically high immigration application fees, the continued policy of indefinite detention, the Byzantine complexity of the rules, the enforced separation of some families, the infamous “Go Home” vans and more. This post is not about those policies, which we cover regularly on this website. They are important and they undoubtedly contribute to a hostile climate for migrants and ethnic minorities.

Here, I want to focus on a fundamental shift in the way that immigration control operates in the United Kingdom. To my mind, the defining feature of the hostile environment of Theresa May is the creation of a system of routine citizen-on-citizen “papers, please” immigration checks as part of everyday life. Historically, UK immigration control was carried out at the border by trained officials. That has fundamentally changed in the last five years, and with very little public debate or dissent.

Private citizens and public servants must now check the immigration papers of other citizens when offering jobs (and even those of existing employees), when renting accommodation, when visiting a GP or hospital, when opening a bank account, when getting married and more. Homeless charities were co-opted into joint working with immigration officials. The police had themselves effectively abandoned immigration law enforcement but immigration officers are now embedded at police stations to check the status of criminals, victims and witnesses and to detain and remove them where feasible.

Every citizen is now a status checker or has their status checked. Or both. Some are more likely than others to be the checker or the checked. The young, old, poor and ethnic minorities are more likely to be checked because they are more likely to rent, move into new jobs, need access to public services or be perceived as potentially illegal. What is the impact on personal and community relations? Does this embed and worsen discrimination against ethnic minorities? Does the government care? I can describe the law and policy and some of the impact but I cannot answer all these questions, unfortunately.

What is the purpose of the hostile environment?

In her interview in 2012 Theresa May set out the broad aims of the hostile environment:

- To discourage people from coming to the UK;

- To stop those who do come from overstaying;

- To stop irregular migrants being able to access the essentials of an ordinary life.

At the time of the introduction of the Bill which was later to become the Immigration Act 2014 and thus the foundation of the hostile environment, then Immigration Minister Mark Harper said the Bill would:

stop migrants using public services to which they are not entitled, reduce the pull factors which encourage people to come to the UK and make it easier to remove people who should not be here.

This is confirmed by the business plan for 2015/16 for the team at the Home Office responsible for implementing and enforcing hostile environment policies, the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate:

Individually these interventions may be seen as just a nuisance but collectively, as we have already seen, they have the ability to encourage illegal migrants to voluntarily leave or never attempt to come to the UK illegally.

These statements tend to tell us how rather than why, though. Are encouraging unlawful residents to leave and denying them access to public services policy aims in themselves or is there a wider purpose?

There seem to have been two high-level policy aims behind the hostile environment:

- Contribute to reducing net migration so that the net migration target of “tens of thousands” might be met; and

- Punish irregular migrants by marginalising, isolating and further criminalising them because it was morally right to do so

These twin purposes are confirmed by internal Home Office priorities. For example, a job advertisement for a “Deputy Director, Illegal Migration, Identity Security and Enforcement Policy” states that a key Home Office aim is to reduce immigration. The first of the overall responsibilities listed is

Driving forward the Government’s agenda to extend compliant environment controls to deter illegal immigration, leverage voluntary departures and protect tax-payer funded services. This includes completing the implementation of 2014 and 2016 Act measures and working with operational partners and across Whitehall to maximise impact and effectiveness of the measures.

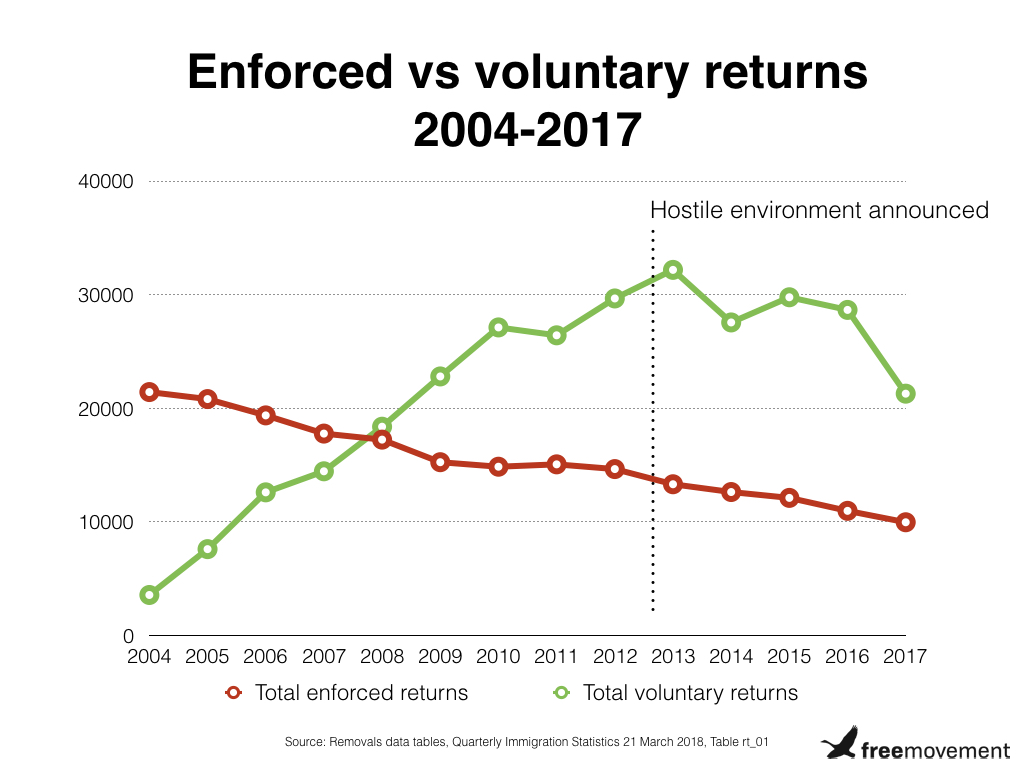

We will look in more detail at whether these aims are being achieved at the end of this blog post. For now, it is sufficient to note that voluntary departures have decreased since the advent of the hostile environment, as have enforced departures; that the Home Office has published no evidence to suggest that the objectives are being met; and that the Windrush scandal has illustrated with a human face that there have been severe unintended consequences of the hostile environment policies. Black and ethnic minority long-term lawful residents have lost their jobs, homes and health. The only known middle-aged, middle-class white person to have lost their job is Amber Rudd, the Home Secretary until April 2018.

What are the origins of the hostile environment?

Carrier sanctions

The first move towards privatised immigration controls by private individuals or companies on one another was made in the Immigration Act 1988 with the introduction of what lawyers call “carriers’ liability”. This law required ferry companies and airlines to check the immigration status of their passengers before carrying those passengers to the United Kingdom. If they carried a passenger without permission to enter the UK then they would be fined. The carrier could avoid the fine if it could show that it had kept a copy of the immigration papers of the passenger concerned and that it appeared “reasonably apparent” the papers were in order.

The carriers were unhappy about this and unsuccessfully challenged the law in court in a case called R v Secretary of State for the Home Department ex parte Hoverspeed [1999] INLR 591.

The fine today is £2,000 per passenger.

In hindsight, the Immigration Act 1988 could be seen as the early beginnings of the modern hostile environment. It established the principle that immigration checks could be carried out by private individuals rather than immigration officers. But it was very far from inevitable that the principle would evolve as it has in the last few years.

Employers

The same can be said in the next tentative step in the evolution of privatised immigration controls, the Asylum and Immigration Act 1996. A new criminal offence was introduced of employing a person who did not have permission to live in the UK. The principle of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks was considerably widened with this new law but the new criminal offence was very rarely prosecuted and changed little in practice.

The prototype for the modern hostile environment is the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006, which introduced a new system of civil penalties for employers similar to the carrier liability scheme. The civil penalties were backed by an amended criminal offence of knowingly employing a person with no right to work.

A civil penalty would be imposed if the employer was found employing a person with no permission to work and the employer had not checked and kept a record of the employee’s immigration papers. Unlike criminal prosecutions, this was an enforceable system. And the new system was enforced. Slowly, at first, but employers were increasingly fined under this law and they started to take the Home Office guidance on immigration checks more seriously.

In 2014, the maximum fine was increased from £5,000 to £20,000 per employee. This is a very substantial incentive for employers to check the immigration papers of their employees, and this is one of the key reasons that the Windrush cases have started to emerge in the last few years. The workplace culture has shifted and immigration papers checks on new and existing employees are now a routine part of human resources policies.

[application]In most cases the job application has been refused or the employee dismissed with no real publicity. There has been at least one case that led to an employment tribunal decision, though: Baker v Abellio London Ltd [2017] UKEAT 0250_16_0510. This appears to be a classic Windrush case. Mr Baker was a Jamaican national who had entered the UK in childhood and who was accepted to have the right to live and work in the UK. Because he was unable to provide his documents, though, he was dismissed.

That is the problem at the heart of the hostile environment: the legislation falsely equates absence of papers with absence of permission and private individuals or companies feel they cannot risk defying the legislation when at risk of a substantial fine.

The Employment Appeal Tribunal ultimately held in Baker v Abellio that employers are not under a legal duty to carry out checks and that it was unfair to dismiss an employee for failure to produce immigration papers when it was agreed that the employee has the right to work. This came as news to many companies, who have misinterpreted the legislation and repeatedly inform their employees that they are obliged by law to check papers. The true legal situation is that employers are not legally obliged to carry out the checks but that they risk a heavy financial penalty if they do not. This incentivises them to “over comply.”

Employer and education sponsorship schemes

Along with direct civil penalties, the other principal plank to the early system of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks was the system of sponsorship introduced with the so-called Points Based System in 2008. The sponsorship system was introduced by means of secondary legislation and changes to the Immigration Rules without the need for an Act of Parliament.

Under the Points Based System, employers and education providers are required to monitor the behaviour of their employees or students, report back to the Home Office and dismiss an employee or student who breaches the rules. Lecturers have to take attendance records and report a student who misses a certain number. Employers have to dismiss and report an employee who has a certain number of unauthorised absences. The compliance of sponsors with their “duties” is carefully monitored by the Home Office and even technical failings can lead to loss of the sponsor licence. Were this to occur, not only would the recruitment of new workers or students be prevented but even existing workers and students would have to be dismissed.

In essence, this is a parallel system of indirect financial penalties on employers and educational providers who are reliant on foreign labour or foreign students. Given that foreign labour and the fees income from foreign students are critical to the success of many major employers and educational institutions, the withdrawal of a sponsorship licence will often have more serious, even existential, consequences than the imposition of direct financial penalties.

Employers and educational institutions have no choice: they have to comply with whatever demands are made of them under the sponsorship system otherwise they will lose their sponsor licence, with disastrous consequences to their business.

The modern hostile environment: the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016

The key moment in the development of the modern hostile environment was the creation of what was initially called the Hostile Environment Working Group in 2012. This involved a wide range of ministers from across government, including care services, employment, housing, schools, justice, health and transport. By building on the perceived success of employer civil sanctions, the idea was to make life in the UK intolerable for those who were unlawfully resident by cutting them off from the necessities of life and preventing access to public services.

The means of achieving this aim was slightly different: to require the production of immigration papers in all walks of life. Here, as we have said, lies the origin of the Windrush problem: the government wrongly equated absence of papers with absence of permission. There is overlap in these groups but they are not identical, as we discuss in the conclusion.

Landlords

The Immigration Act 2014 introduced a system of landlord civil sanctions similar to the existing scheme for employers. A landlord would have to check the immigration papers of a potential or existing tenant against a list provided by the Home Office and refuse a tenancy to or evict a tenant whose papers did not match those on the list. In the event of confusion, a landlord could call a Home Office helpline to check the immigration status of the person concerned.

The scheme was toughened further by the Immigration Act 2016, which introduced a criminal offence for landlords and agents of renting property to a person knowing or having reasonable cause to believe that the person is disqualified and a system of accelerated eviction where the Home Office serves a notice on a landlord.

The new offence is broadly drawn and creates issues for legitimate schemes that provide safe housing for vulnerable individuals such as victims of abuse, as well as for those with friends and family living with them. The government response to this issue has been to suggest that such people, even though they fall within the terms of the offence, are not likely to face prosecution as the scheme is designed to target “rogue landlords” who exploit migrants.

This is a startling admission. The government has deliberately created an overly broad criminal offence which it does not intend to have universal application and which will instead be mitigated by selective prosecution. This is a recipe for discrimination and abuse of power by officials.

The eviction provisions, allowing landlords in some cases to evict without a court order, leave individuals, including children, entirely at the whim of the Home Office and the accuracy of the information held in its databases.

There is every incentive under the right to rent scheme for a landlord to be overzealous. As Paul Daly writes over at Administrative Law Matters:

There are penalties for failure to enforce the immigration laws but no prizes for enforcing them correctly. Any rational landlord will refuse to let a premises to a prospective tenant when unsure about his or her immigration status.

The Right to Rent scheme therefore encourages landlords to be cautious in renting property to those they perceive might not have the right to rent. Some landlords might well think that ethnic minorities or foreign looking or sounding people are “high risk” whereas white people with local accents are “low risk”.

Banks and building societies

In her 2012 interview announcing the “hostile environment” Theresa May said that

If you’re going to create a hostile environment for illegal migrants … access to financial services is part of that.

Sections 40 to 42 of the Immigration Act 2014 created a scheme intended to prevent people from opening bank accounts if they do not have permission to live in the UK. The bank or building society is required to check the status of each new potential customer with a specified anti-fraud organisation or a specified data-matching authority.

Those acting as the immigration officials in this case are the banks and building societies which hold the accounts, and who must undertake an immigration status check on any person applying for a current account.

An inspection report on the operation of these provisions found that the organisation designated for checks was CIFAS, but that the data held by CIFAS was not always accurate because the underlying Home Office information was not correct. In a sample size of 169 cases, inspectors found that 10% of the people on the list were wrongly listed as irregular migrants. They had leave to remain, an outstanding application for leave or an outstanding appeal.

Despite the flaws in the data on which decisions would be made, the Immigration Act 2016 developed the banking rules even further. New rules require banks and building societies to make checks on existing account holders if requested to do so by a specified body, and to notify the Secretary of State if the person may be a “disqualified person” (basically, an irregular migrant).

Not being able to open a bank account is one thing; having your existing account closed is quite another. This may well render you destitute, homeless and jobless.

Marriage

The Immigration Act 2014 also introduced new requirements for marriage registrars to report suspected sham marriages and increased the notice period for all marriages from 15 to 28 days for the explicit purpose of enabling Home Office oversight.

The Home Office expected 35,000 marriages per year to be referred to the Home Office for consideration and 6,000 actual investigations to occur per year. A subsequent inspection report found that actual referrals and investigations were much higher. For the six-month period March to August 2016 inclusive, 23,948 marriage notices were referred to the Home Office team responsible, the Marriage Referral Assessment Unit. Of those, 17,818 were allowed to marry at 28 days and 6,130 were forced to wait the 70-day extended period.

The number of sham marriages per year is thought to be tiny. The changes to the marriage requirements wrought by the Immigration Act 2014 are one of the starkest examples of a change to the rules for all citizens introduced for the purpose of targeting the tiny minority of cases of abuse.

Driving

The Immigration Act 2014 conferred on the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency a power to revoke a driving licence when issued to a person who does not have leave to remain. Where a person’s licence is revoked on this basis, it is not open to them to argue in an appeal against the revocation that leave should have been granted to them, or that they have been granted leave after the date their licence was revoked.

The independent inspection report on the hostile environment examined the use of these powers. The Home Office made 9,732 revocation requests to the DVLA in 2015, all but meeting the target of 10,000 per year. Some of these were wrongly revoked: the person actually qualified for a driving licence after all. In 2015, 259 licences then had to be reinstated. In the meantime, those affected would have been unable to drive or would have committed the strict liability offence of driving without a licence.

A further problem emerged with notice of revocation being sent to people who had left the UK, meaning the notice was unlikely to be received. Such individuals would be committing an offence if they were to drive on return to the UK, perhaps without ever knowing that their licence had been revoked.

The Immigration Act 2016 went further by introducing a power for the entry and search of premises for a driving licence if it is reasonably believed that a person who is not lawfully in the UK holds it and creating a new offence of driving when unlawfully in the UK. It creates rights for law enforcement to detain the motor vehicle in question, as well as the offender.

Employers

A number of changes to the civil sanctions system for employers were possible without the need for primary legislation. The increase in the maximum penalty from £5,000 to £20,000 was achieved through changes to regulations, for example.

[ebook 22148]The number of employer prosecutions had remained low under the 2006 Act; according to the Crown Prosecution Service, there were fewer than 100 prosecutions in the five years to 2014. It is not known how many of these resulted in a conviction. Perhaps as a result, the offence was amended by the Immigration Act 2016 to enable easier prosecution. Employers can now be prosecuted under the amended provisions where they knew, or had reasonable cause to believe, that they were employing an illegal worker.

The hostile environment, public services and civil society

We have seen that the defining features of the hostile environment are citizen-on-citizen immigration checks in everyday life. Primary legislation in the form of the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016 was necessary to introduce some of these checks. In other walks of life the checks could be and were introduced by secondary legislation and bureaucracy.

Operation Nexus

Operation Nexus is an institutional arrangement between the Home Office and police forces whereby immigration officials are embedded at police stations. Suspected immigration offenders are referred by the police to the Home Office rather than being arrested and prosecuted for immigration offences. Instead, they are simply detained and removed.

Nexus began as a project in London targeting suspected criminals and gang members considered by the police to be high risk. The standard of proof to deport a person is lower than to convict them, enabling easier and cheaper removal of individuals the police considered undesirable. The project was apparently deemed a success. It was broadened out to all suspected unlawful residents and rolled out nationally.

There have been concerns about the impact Operation Nexus has on community relations. Rita Chadha, Chief Executive of the Refugee and Migrant Forum of East London, said this in a Guardian article on Operation Nexus in June 2013:

When Nexus first began we were reassured it was only about people who had criminal convictions in this country or in their home countries and who were very high risk.

What we are seeing now is that they are targeting all crimes and low level criminality. This is going to stop victims coming forward in the black and ethnic minority communities because they fear they will be targeted by Nexus. If you have a woman suffering domestic violence in a household of overstayers she is not going to come forward.

This is totally going to mess up local policing and any trust communities have in the police.

In April 2017, the Metropolitan Police confirmed in response to a Freedom of Information request that it passes on people’s personal details where there are concerns over immigration status, even when such people are the victims or witnesses of crime. In November 2017 it was reported that a victim of kidnap and rape was arrested for immigration offences when she sought help and then referred by the police to immigration officials for removal.

Homelessness

In a March 2017 report, Corporate Watch revealed that charities such as St Mungo’s, Change, Grow, Live and Thames Reach conduct joint “visits” with Immigration Enforcement officers; and that they pass information on the locations of rough sleepers to the Home Office.

The Corporate Watch report found, after submitting Freedom of Information requests to local councils, the Home Office and the police, that there were

141 such patrols organised by the GLA [Greater London Authority] and 12 London boroughs last year. This figure does not include Westminster, the biggest concentration of London homelessness, where patrols are likely to be even more frequent.

Joint visits in just eight of these areas led to 133 rough sleepers being detained, while 127 people were deported in under a year in Westminster alone.

In fact, such joint visits are not new. The report says

The first pilot scheme we are aware of was Operation Ark, in 2010-11. This also took place in Westminster, and also involved St Mungo’s and Thames Reach.

But it seems that efforts increased in 2015 and 2016. A Greater London Authority called the “Mayor’s Rough Sleeping Group” (MRSG) was developed in 2015 and collaboration around non-UK rough sleepers was discussed regularly through 2015 and 2016. The group brought together officials from the Greater London Authorities and central London boroughs, the Metropolitan Police and Home Office, and managers from charities St Mungo’s and Thames Reach, Homeless Link and Crisis.

In November and December 2015, Westminster ran a key pilot project with the Home Office called Operation Adoze, which resulted in 127 EEA citizens being removed from the UK.

The Corporate Watch report of March 2017 also disclosed information sharing between homelessness charities and the Home Office:

Outreach teams [of homelessness charities] also routinely pass on locations of non-UK rough sleepers to ICE, including through the London-wide CHAIN database, and through local co-operation agreements. The GLA has contracted St Mungo’s and Thames Reach under “payment by numbers” schemes where fees depend on the number of rough sleepers they get out of the country.

Again, this dates back to May 2015, when the agreement to share data was made between the Greater London Authority and the Home Office.

On its website, St Mungo’s accept that they have indeed worked with the Home Office:

In areas where local authorities have decided to engage the Home Office to take action against individuals or groups of rough sleepers, St Mungo’s outreach teams work alongside the Home Office teams to provide support and advocate on behalf of vulnerable individuals. This decision to be present on the street during such operations means we can ensure that the best solution for vulnerable people is sought and that any work being done with individuals to resolve their homelessness is not jeopardised by Home Office interventions.

The underlying Home Office policy of targeting rough sleeping EEA nationals for removal was ultimately declared unlawful in the case of R (Gureckis) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] EWHC 3298 (Admin). Although the policy ultimately ended, this joint working between the Home Office and some elements of civil society bears all the hallmarks of the hostile environment.

Health care

Since 1977 there has been legislation permitting the charging of non-residents for NHS services. The first regulations enabling this to occur were introduced in 1982 and further legislative changes were made in 2006. However, very little if any money was recovered from non-resident users of NHS services.

New regulations were introduced in 2015 (and strengthened in 2017) with the intention of changing this by forcing hospitals to carry out immigration checks and impose upfront charges for treatment to those who were not eligible for free care. It is these changes that caused “Albert Thompson” (he now goes by his real name of Sylvester Marshall) to be denied cancer treatment by his local hospital despite lawful residence of 44 years.

The hostile environment in health care does not just manifest in immigration checks. Data sharing between the NHS and Home Office was formalised in a Memorandum of Understanding in January 2017. This facilitates the transfer of limited non-clinical patient information about “immigration offenders”. The memorandum itself states that it is not “legally binding” but “simply documents the processes and procedures agreed between the participants”. The NHS is permitted to disclose information under section 261 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 where the disclosure is made in connection with the investigation of a criminal offence.

In the first eleven months of 2016 it was reported that 8,127 requests for patient information had been made by the Home Office.

Education

We have already seen that private schools and higher and further education providers have in effect been required to carry out immigration checks and supervision on students as the quid pro quo for being permitted to recruit lucrative foreign students. This was achieved through the sponsorship scheme of the Points Based System.

More recently, the Home Office attempted to co-opt ordinary schools as well.

On 1 September 2016, the Education (Pupil Information) (England) (Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2016 (SI 2016 No. 808) came into force, adding “nationality, country of birth, and proficiency in speaking, reading, and writing in English” to the list of data to be collected by schools. This data was collected through the annual schools’ census and collated in the national pupil database.

Activists such as the organisation Against Borders for Children immediately raised suspicions about this new requirement. They were concerned that the data would be shared with the Home Office for immigration enforcement purposes. They ran a campaign to inform parents that they could refuse to answer these questions.

Fears that these details would be passed on to the Home Office were confirmed when the Department of Education responded to a Freedom of Information request by disclosing that details of individual children on the national pupil database in England and Wales were passed to the Home Office 18 times in four years. A memorandum of understanding between the Department for Education and the Home Office was also released in December 2016 following a Freedom of Information request. It confirmed that the education department would share pupils’ names, recent addresses, school and some attendance records, including earliest and latest attendance dates.

Unusually as far as the hostile environment was concerned, the government reversed course. In April 2018 the Department for Education announced that it would end the collection of nationality and country of birth data in schools.

What has been the impact of the hostile environment?

The stated purpose of the hostile environment is to drive down inward migration to the UK by making it as disadvantageous, risky, expensive and inconvenient as possible. The hostile environment is also intended to encourage migrants already in the UK to leave by administering many into irredeemable illegality and making their lives as marginal and difficult as possible.

Given the impact of the hostile environment on the lives of some citizens, its breadth across government and the cost of implementing it, it might be expected that the success or otherwise of the policy would be carefully monitored. Not so.

We shall see that part of the reason that there is no evidence that the Home Office is not interested in the question of whether it actually works or not.

Does the hostile environment encourage voluntary departures?

The Home Office publishes immigration statistics every quarter. The statistics include data on enforced and voluntary departures. This data suggests a fall in both:

In his inspection report on the hostile environment, the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration found that:

There was no evidence that any work had been done or was planned in relation to measuring the deterrent effect of the ‘hostile environment’ on would-be illegal migrants.

No targets had been set by ministers for voluntary returns or net migration and there was no pressure to deliver specific outcomes.

Revealingly, the inspectors were told by civil servants that even if there was research to show that the hostile environment was not effective, the policy would not be abandoned:

This was because it was the right thing to do, and the public would not find it acceptable that illegal migrants could access the same range of benefits and services as British citizens and legal migrants.

Similarly, a specific separate report by inspectors on the “Right to Rent” measures targeting landlords found that

Overall, the RtR scheme is yet to demonstrate its worth as a tool to encourage immigration compliance (the number of voluntary returns has fallen). Internally, the Home Office has failed to coordinate, maximise or even measure effectively its use. Meanwhile, externally it is doing little to address stakeholders’ concerns.

The hostile environment is avowedly intended to discourage migration but there is no evidence to suggest it works, no targets have been set, no evaluation is being commissioned and the expense of implementation may outweigh the income generated.

The hostile environment has the flavour more of moral crusade than evidence-based policy.

Denial of health care and public services

The hostile environment is intended to deny work, money, housing and public services to illegal migrants in order to force them to leave the country. We have already seen that the policy does not appear to force migrants to leave the UK. In the meantime, though, what is the human impact of this denial of the basics of life? What does it mean to create an illegally resident underclass?

Consider the impact of immigration checks combined with upfront charges for NHS care combined with data sharing with the Home Office. What are the consequences if some residents of the UK and their children, whether they are lawful or unlawful, are unable (or, for fear of the possible consequences, unwilling) to access doctors?

Some conditions are strictly personal, such as cancer. Rather than such a condition being caught early and treated, the victim may die prematurely. There are reports of very ill patients wrongly being turned away by hospitals and pregnant women being afraid to seek antenatal care for fear of the immigration consequences, with obvious risks to their health and the health of their babies.

Other conditions are contagious or have wider public health implications. It is critically important that vaccination rates are very high, for example, and that conditions such as HIV or tuberculosis are identified and treated. By denying healthcare to afflicted people and/or making them scared of going to the doctor, it is arguable the hostile environment represents a risk not just to individuals but to public health.

Is the price of hostility one worth paying? The policy is creating an illegal underclass of foreign, mainly ethnic minority workers and families who are highly vulnerable to exploitation and who have no access to the social and welfare safety net that protects not just individuals but the fabric of society.

Does the hostile environment save money and protect public services?

The nature of the hostile environment as a privatised system of immigration controls means that the costs of administration fall to a significant extent on private citizens and companies. It is impossible easily to quantify the financial burden borne by private individuals and companies, and therefore ultimately, if indirectly, by the British public. But it must be huge.

The direct costs of creating the necessary bureaucracy to enforce privatised immigration checks are also hard to estimate. Some data is available on the direct cost to the Home Office, however.

On an operational level, the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate (“ISD”) is responsible for enforcing the hostile environment. It has existed since June 2013 and was reported in 2016 to have a staff of 146 and a budget in £5.5 million in 2015/16. Its stated purpose is to “to encourage greater compliance with the immigration rules”. A Freedom of Information request in 2013 revealed the nature of its work:

The unit has overall responsibility for removing incentives for people to stay illegally and encourage those who are in the country unlawfully to regularize their stay or leave the UK. This is achieved by ensuring a range of interventions and sanctions are systematically applied to deny access to services and benefits for those who are unlawfully in the UK. The unit works closely with government departments and a range of other partners across the public and private sectors to identify those migrants accessing such services and benefits to which they are not entitled. I&SU also has responsibility for the issuing and collection of financial penalties to those employers found to be employing illegal workers and the subsequent debt recovery process through third parties.In short, the purpose of the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate is the indirect enforcement of immigration control through third parties.

The Home Office is not the only department to expend substantial resources on hostile environment immigration checks. The idea behind the hostile environment is presumably in part to “save” public services from the supposed costs of providing services to unlawful residents and visitors.

There is very little evidence as to what the costs to public services might be of implementing the system of checks required by the hostile environment might be but if we look at health care the cost of administering the system is thought to outweigh the supposed benefits. Professor Martin McKee, Professor of European Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, gave evidence in February 2017 to the House of Commons Health Select Committee. He told the committee that his research team had just completed

a study, which is under review at the minute, where we submitted freedom of information requests to every acute trust in England to ask them how much they spent collecting money from overseas patients and how much they recovered. Most of them were spending more money than they were recovering. They had a very low level of recovery, but as time went by they found they were often trying to recover from people who were entitled anyway.

It is counterproductive if a policy supposedly intended to save public services from unquantified abuse by unlawful residents and visitors actually ends up costing the public purse more than it saves. This is before the other human costs of the policy are weighed in the balance.

Does the hostile environment affect the “wrong” people?

We have seen that the hostile environment has not increased voluntary departures, may have cost more than it has saved and in doing so has made the lives of some people miserable. It has failed in its high level objectives, but has it adversely affected the “right” people, its intended target of unlawful residents?

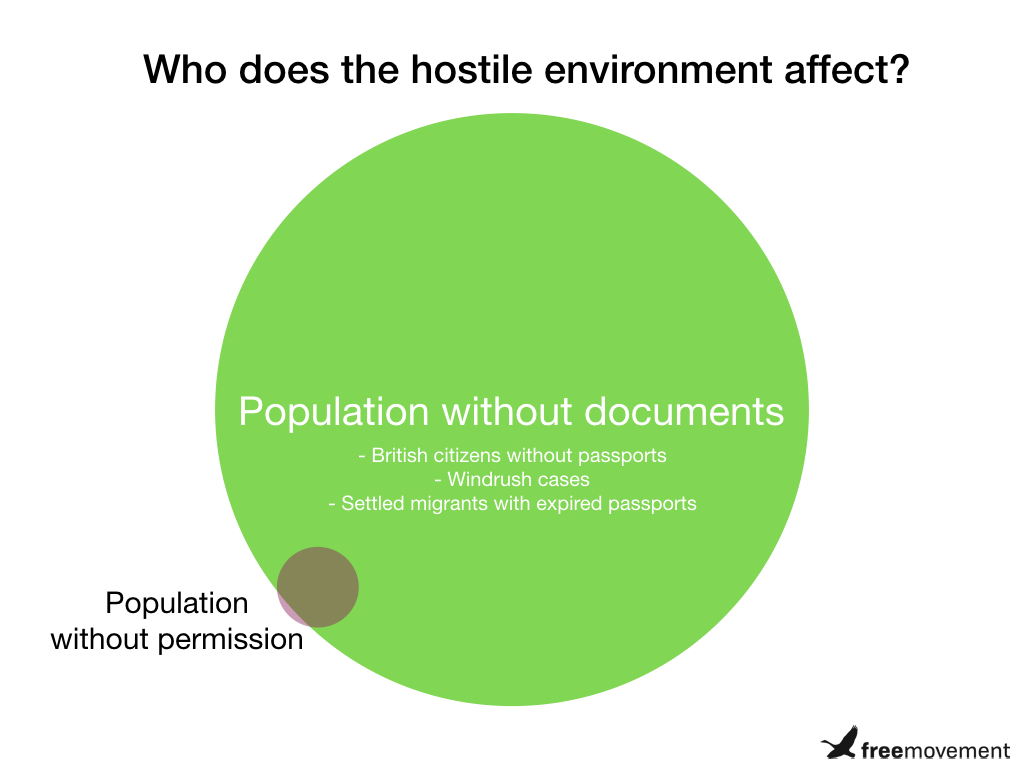

The basic, underpinning assumption of the hostile environment approach is that unlawful residents do not possess immigration papers and therefore by targeting those without immigration papers it is possible to target unlawful residents.

It is true that most unlawful residents do not have immigration papers, although some may well possess forged or false documents. The problem is that there are rather a lot of lawful residents who also do not have immigration papers.

This includes the Windrush generation of Commonwealth citizens who were already living in the UK before the Immigration Act 1971 came into force on 1 January 1973. It also includes an estimated 9.5 ordinary residents of England and Wales who do not possess a passport and many migrants who have lived in the UK for years but whose old passports or immigration papers have expired. The size of the population without permission is unknown but we know that the population without documents runs into the millions.

The hostile environment has required many people to apply for passports, not in order to go on holiday to other countries but to live within their own country.

There is another group of residents adversely affected by the hostile environment for whom many members of the public would feel sympathy: the accidentally unlawful. The accident may be theirs or it may be that of the Home Office.

The boundary between lawful and unlawful has been blurred by the increasingly complex and arbitrary immigration rules. These have been repeatedly condemned by lawyers and judges as unfit for purpose, with one senior judge describing them as “an impenetrable jungle of intertwined statutory provisions and judicial decisions.” (Lord Justice Jackson in Sapkota [2011] EWCA Civ 1320.)

For example, if a skilled worker’s immigration application is refused and he or she wishes to challenge that decision in court, that worker’s immigration status will lapse while the challenge is brought. The person must stop working, his or her bank account can be closed and so on. Where an application is made and the fee is not properly processed or the accompanying photograph is adjudged to be against an insufficiently white background, the application can be treated as invalid and the applicant’s lawful status lapses.

Home Office civil servants also struggle with the complexity of immigration law. The appeal success rate has reached 50% of appeals lodged. Not all refusals are appealed, but for such a high proportion of appeals to be allowed suggests some very serious problems with the quality of decision-making at the Home Office.

These accidentally unlawful migrants are subjected to the full force of the hostile environment despite their attempts in good faith to comply with the rules. The lives they have built for themselves and their families can be ruined and they can be forced to leave because of a simple error on their part or, worse, an error on the part of the Home Office.

Policy-makers fail to recognise how easy it is to fall foul of complex Home Office rules and regulations.

Does the hostile environment cause discrimination?

Ministers state that the hostile environment is aimed at illegal immigrants. There are concerns that the effects are far more widely felt.

The most studied of the hostile environment policies so far, perhaps because it is the most controversial of all, is the “Right to Rent” scheme. The risk that some landlords will discriminate against black and minority ethnic people on the basis that they might not have the right to rent is obvious.

The Home Office commissioned research into these risks when the scheme was being piloted in the West Midlands in 2015 and did indeed find that BAME tenants were more likely to be asked for their immigration papers and that some landlords displayed potentially discriminatory behaviour or attitudes.

The same research revealed that British citizens without a passport, older people without photo ID and younger people on low incomes were at risk of being prejudiced by the scheme, as were lawful migrants and “any foreigners”.

Later independent research by the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants showed that the prejudicial impact is real. JCWI conducted a mystery shopping exercise and the results showed significant discrimination against a lawful settled migrant compared to a British citizen:

Harinder stated that he was a British citizen and that he had a British passport, while Ramesh stated that he was a non-British citizen who had settled status/indefinite leave to remain in the UK demonstrated through his Home Office document. Both scenarios had an unlimited/permanent right to rent in the UK.

Ramesh received 12% fewer responses to his enquiries (51% compared to 58% of enquiries). He was also 15% less likely to be told by a landlord that the property was available (33% compared to 39% of enquiries). Overall, Ramesh received a negative response or no response to his enquiry more than half the time (55%), and was 20% more likely not to receive a response or to receive a negative response than Harinder (46%).

For the government to introduce a new law that increases discrimination against minorities and to do so knowingly is a very significant departure from the presumed consensus that the role of modern government is to promote equality of opportunity.

What would it take to undo the hostile environment?

The Home Office attempted to relabel the “hostile environment” as the “compliant environment” in 2017 and the new Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, wasted no time endorsing the new branding. There are various earthy phrases available to describe the redressing of one thing as another but suffice it to say that without the reversal of the laws underpinning the hostile environment, nothing much is going to change.

The hostile environment is deeply embedded in primary and secondary legislation and increasingly embedded in British culture. Rolling back the principle of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks would require repeal of significant portions of several Acts of Parliament, not least the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016.

[ebook 33879]Some aspects of the policy are more obviously offensive than others. Some are more recent and therefore arguably easier to reverse. For example, there is strong evidence that the right to rent provisions of the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016 are causing discrimination in the housing market and these could be repealed in the upcoming Immigration Bill. Landlords and tenants alike would celebrate such a move. Similarly, the laws requiring banking and driving licence checks could be repealed.

Many aspects of the hostile environment could be undone with changes to secondary legislation and Home Office practice. Intrusive immigration checks and upfront changes in the NHS could be reversed and would save public funds, for example.

Home Office interference in weddings, policing and homelessness could easily be ended or at least significantly scaled back. Considerable sums of money must have been spent on these initiatives yet the Home Office has little or nothing to show for them on a policy level. The public was probably alarmed more than reassured and it seems unlikely there was any significant macro level impact on net migration or migrant behaviour generally. A few more migrants may potentially have been deported, which some would argue is a moral virtue in itself, but no public cost/benefit analysis has been conducted and the increased state interference in all walks of life has not been weighed in the balance.

With thanks to Melanie Griffiths and Nath Gbikpi for their assistance with parts of this blog post.

SHARE