- BY Colin Yeo

Free Movement review of the year 2018

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

Windrush

The defining event of 2018 in the world of immigration law was without doubt the exposure of what has become known as the Windrush scandal.

The way the scandal was eventually picked up by all news outlets caught everyone by surprise, me included. It has led to significant changes at the Home Office — albeit so far only affecting numerically small groups of people — and, along with the impending exposure of EU citizens to the same immigration regime, has also led to talk of a more migrant-oriented immigration system.

Like other immigration lawyers, I knew that people must be affected by the hostile environment policies but I did not myself have any affected clients. Those most affected rarely if ever came to lawyers, or st least immigration lawyers, for help. This shames us as a profession, in my opinion. With legal aid unavailable, our fees unaffordable to someone who has lost their job and pro bono help hard to come by, it took the work of a journalist, Amelia Gentleman, to bring the scandal to public attention. Fantastic charities like JCWI, Praxis and Migrants Resource Centre did what they could. But where were we lawyers?

The only known white, middle class, middle aged individual to lose her job due to the hostile environment policy was Amber Rudd, then Home Secretary. Her replacement, Sajid Javid, promised to use citizenship deprivation powers more widely and was so flustered by a few refugees per day crossing the Channel that he appointed a “gold commander” and declared it a “major incident”. He also put on hold some aspects of the hostile environment policy, including automatic bank account closures. If or when these may resume is unknown.

''Javid also appointed a gold commander…" because our migration 'policy' is basically a Game of Thrones fantasy administered through the Duke of Edinburgh scheme. https://t.co/kNIkBgRRUI

— Lyndsey Stonebridge (@LyndseyStonebri) December 29, 2018

The immigration appeal success rate exceeded 50% for first time ever, although the Home Office belatedly seems to be taking steps to reduce that by reviewing and conceding some appeals at an earlier stage. Meanwhile, average waiting times for these appeals continued their seemingly inexorable rise. Perhaps the recruitment of up to 41 immigration judges at a salary of £108,171 (more in London) will turn things around.

Deaths at sea

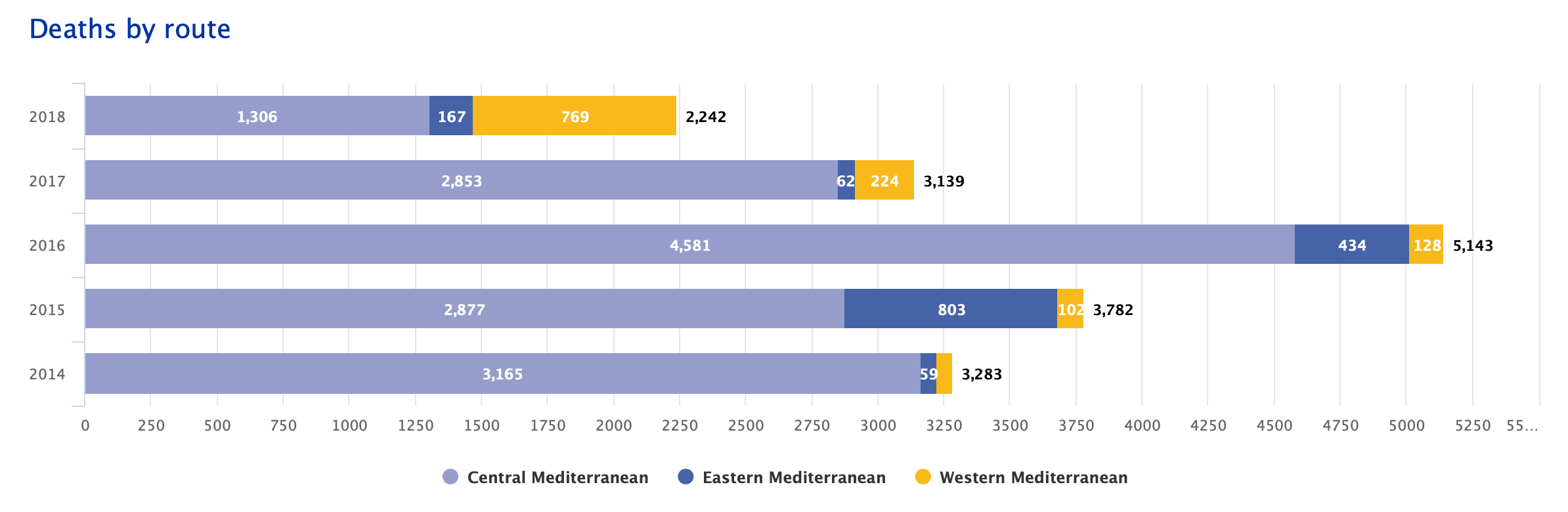

It is thought that 2,242 migrants died at sea in the Mediterranean in 2018. This is a drop on last year and less than half the total of 2016 but it is still an horrendously high number. The chart below is from the IOM’s Missing Migrants Project.

These deaths are avoidable: they are caused by the barriers the EU has raised around itself and the absence of safe routes for asylum. With a reported increase in the number of refugees crossing the English Channel at the end of the year, it seems only a matter of time before there are deaths at sea closer to home.

While on this tragic subject, it would be remiss not to mention the excellent, humanising and much needed work of the Last Rights project, founded by retired Upper Tribunal Catriona Jarvis and her husband Syd Bolton.

EU citizens rights

By the end of 2017 we knew the outline of the EU citizen settled status scheme. Despite having nearly 20 years of cynicism hammered into me by day to day experience of Home Office decision making, I still struggle to believe that our Government is really forcing over 3 million of our friends and neighbours to apply to remain in their homes and is charging them for this downgrading of their rights.

But that really is what the current settled status scheme involves and there is no sign at all of the Home Office reversing course, no matter how many hundreds of thousands of EU citizens and family members may be rendered illegally resident when the deadline passes.

The application process will be open to all from later in January. The pilot testing seems to have gone OK but so far it has not been tested at anything like the required scale, the main test subjects so far have been employed with public sector organisations (meaning of course they show up on cross-checked Government records) and yet there are already worrying signs that a significant number of existing applications remain undecided and feedback has not been universally positive.

My prediction for 2019 is that there will be serious teething difficulties with the settled status application process once it is opened to all, this is going to cause huge anxiety to a significant minority of applicants and nothing like the necessary number of EU citizens and family members will be processed by the end of the year. Worse, the underlying premise on which the whole process is based is wrong because not everyone entitled to apply will actually apply. The Home Office will press ahead regardless and the end result will be that hundreds of thousands of EU citizens and family members will be left living illegally in the UK. By its nature this will not be immediately obvious, but it will gradually become apparent after 2020.

I sincerely hope I am proved wrong on this.

Immigration law

The Law Commission is rumbling on with its immigration rules simplification project and it looks like there may be a consultation in the new year with a full report to follow in 2019. Amber Rudd has said that simplifying the rules was a priority for her but we’ve heard nothing similar from her successor.

We saw several Supreme Court judgments on immigration law in 2018 and I will pick out the three big ones. You can check out our case law hub to see our case law articles organized by court.

In Romein [2018] UKSC 6 the Supreme Court cut through the Gordian knot of statutory interpretation to open up the prospect of belated recognition as British citizens for the children of British women born between 1949 and 1983.

KO (Nigeria) [2018] UKSC 53 was another of their Lordships Delphic pronouncements on the best interests of children. While the court was seemingly clear that children should not be penalised for the bad behaviour of their parents, Lord Carnwath muddied the waters by suggesting that the fact the parents have no immigration status is relevant to whether it is reasonable for a child to leave the country. More litigation on this question is inevitable, and I think we all know which way the Upper Tribunal and Court of Appeal will jump.

The statutory human rights presumptions Theresa May introduced with the Immigration Act 2014 finally reached the highest court. In the case of Rhuppiah [2018] UKSC 58 Lord Wilson, giving the court’s judgment, held that a “precarious” immigration status was anything short of settlement and hinted that even settlement or citizenship might be considered precarious if jeopardised by the holder’s deception or criminality. “Financial independence” was interpreted consistently with previous authorities as meaning not having recourse to public funds rather than having a job and assured income.

Less said about the Court of Appeal the better.

Here on Free Movement

In 2018 we published 516 articles and over half a million words. That feels like a lot. CJ took over a great deal of the day to day writing, commissioning and editing work, enabling me to create more courses for members. A huge thank you to CJ, to Faye, who is now the website’s main point of contact for enquiries and members, and to all the contributors this year.

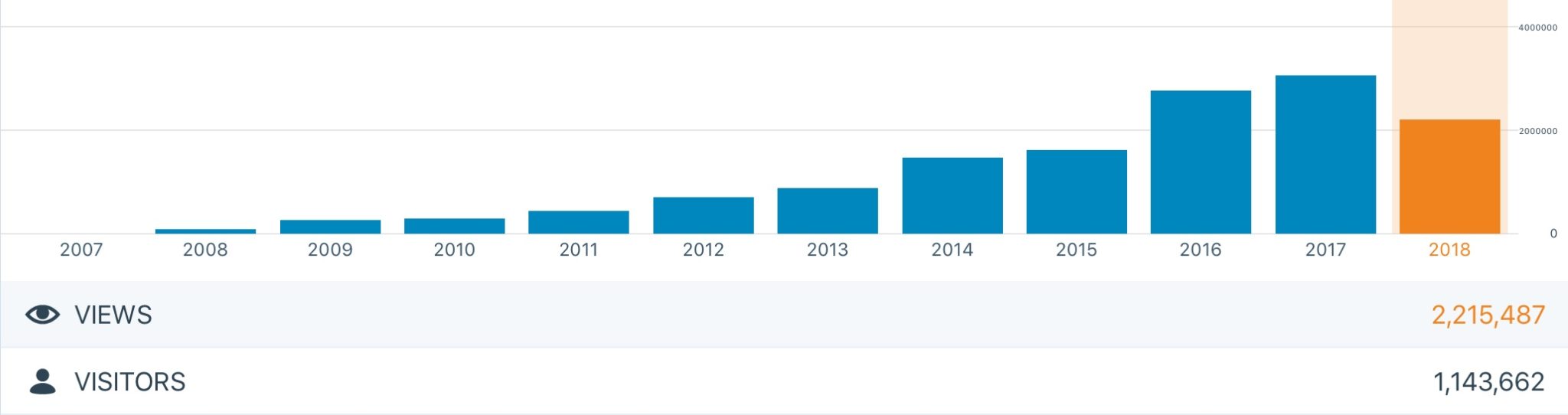

Our total number of page views here on Free Movement has now topped 14 million. Annual readership actually fell for the first time from what I imagine will prove to be an all time high in 2017. Free Movement readership grew hugely from June 2016, after the Brexit referendum, and has been gradually declining since then.

There were fewer one off visitors, but active paying membership numbers increased substantially, from 1,560 at this time last year to over 2,300 at the end of 2018.

The email list stands at 17,240, which looks like a fall on last year, except that I purged about 2,000 inactive subscribers at the time of GDPR commencement in April 2018. So we’ve picked up about 2,000 new email subscribers this year, I think.

Our social media presence is strong, with my own @colinyeo1 Twitter following at 17,700 or so (I’ve picked up hundreds of new followers since I started writing this post because of a thread I put out on the “crisis” in the Channel), @freemovementlaw at 2,215, @immigrationbot at 2360, 5,700 ‘likes’ on our Facebook page and 277 followers on our new LinkedIn company page we started this year (so I could stop bombarding personal contacts with immigration stuff!).

Future migration

The year 2018 heralds a major inflection point in UK immigration policy. This is the year — but only just — that saw the publication of an important White Paper on immigration as well an Immigration Bill. Once enacted, the two combined will have an impact on migration to the UK unseen since the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 ended free movement around the Commonwealth.

Yet the hindsight of history will no doubt attribute these changes to 2019, the historic year that Brexit is due to happen. This will be right and proper; the White Paper and Immigration Bill are both sideshows to the main event: Brexit and the end of EU free movement.

Considering that this is supposed to be what “taking back control” looks like, the White Paper seems to me to lack any clear, positive Big Idea or guiding principle aside from abolishing EU free movement. Theresa May, in her miserable foreward to the document, tells us that “we can reduce the number of people coming to this country”. Who cares what Theresa May thinks these days, given that she is self evidently on the way out? Home Secretary Sajid Javid makes no such comment in his own foreward, instead saying merely that the new system will be skills-based and allow for “control.”

If there is a theme aside from ending free movement, it is that it will be easier in future to employ skilled migrants. If we ignore the very important fact that it will be a lot harder to employ skilled migrants from the EU. The media focus tends to be on unskilled labour from the EU but there are many skilled workers who come too. Our hospitals, for example, are blessed with many doctors from the EU, who can currently just apply for and get a job here and know that their pension rights and so on are transferable. In future, they will need to make very expensive and complex immigration applications with, probably, no transferable social entitlement arrangements. Many simply won’t bother when their talents easily can be deployed in plenty of EU countries. And that’s where some of the most acute economic and other damage from Brexit will come.

The White Paper proposes to scrap the quota on skilled workers, abolish the resident labour market test (requiring jobs to be advertised domestically before they can be offered to migrants) and lower the level of academic or vocational qualifications required for entry. The work permit salary threshold may or may not be maintained at £30,000 as a very crude proxy for determining whether employment is “skilled” or not. Some rather vague assertions are made that the bureaucratic burdens on employers will be reduced, but given that this comes from the same people who brought us the Byzantine insanity of the Points Based System, Appendix FM and Appendix V, those words seem likely to prove worthless.

Collectively, these changes, if they occur, would make it theoretically easier than at present to employ foreign skilled workers. But the Immigration Skills Charge will be retained as a disincentive to employers, immigration application fees are likely to keep on going up and up and the Immigration Health Surcharge will be doubling in January and may well rise further in future.

That is all for the future, though. Even if there is no Brexit deal the Home Office will be incapable of implementing this new system until 2020. So, while the year 2019 will certainly be historic, it is likely to be at least 2020 before we see major changes to immigration policy implementation.

In the meantime I leave you with the Three Laws Of Brexit:

The Three Laws Of Brexit:

1. It is ALWAYS someone else’s fault.

2. Whatever you said earlier wasn’t what you meant.

3. Details don’t matter. https://t.co/ajC2FertRd

— Colin Yeo (@ColinYeo1) December 31, 2018

SHARE