- BY Colin Yeo

What do immigration officers look for when assessing visit visa applications?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

“Two visas had been rejected … I was wrenched by a heavy feeling of humiliation…trying to prove that I’m a “normal person” like any Englishman, that I’m not aspiring to swap my career in Egypt as a cartoonist [and] scriptwriter … for British social welfare, that I really want to see my wife’s grandmother who is really old, and that’s it.”

– Andeel, Egypt (taken from an article featured in Mada Masr, an Egyptian online newspaper)

In the year to September 2016, UK immigration authorities received almost 2 million applications for visit visas. Just over 15% of these applications were rejected.

That is almost 300,000 decisions to refuse entry.

We take a look at the guidance given to the officials making these decisions, the remedies available in the event of a refusal, and what kind of evidence might improve a UK visit visa application.

What do the visit visa rules say?

The regulations governing the entry of visitors to the UK are set out at Appendix V of the immigration rules. They define a visitor as

a person who is coming to the UK, usually for up to six months, for a temporary purpose, for example as a tourist, to visit friends or family or to carry out a business activity

The ‘business activity’ mentioned refers to a limited number of permitted activities set out in Appendix 3 of the rules. Any work outside of these restricted activities is not permitted by visit visa holders and would be considered a breach of the conditions of leave.

Visitors are generally split into two categories:

- Visa nationals, who need to be issued a visa before they travel to the UK; and

- Non-visa nationals, who can be issued with a visa upon arrival at the UK border.

The list of visa-national countries is contained at Appendix 2 of the rules. The person making the decision as to whether to grant entry to a prospective visitor is referred to as an Entry Clearance Officer (ECO). The ECO will be considering whether an applicant satisfies the requirements set out in the rules, which consist of two broad categories: suitability and eligibility.

Suitability

The ‘suitability’ criteria actually relate to applicants who might be considered ‘unsuitable’ to have in the UK. The two main categories of applicant who might be considered unsuitable are:

- those with a criminal record, and

- those who have previously breached UK immigration law.

There are a few other situations where applicants may be considered unsuitable, for example where they have unpaid bills totalling more than £500 from the NHS, or have engaged in litigation with the Home Office and failed to pay the costs of that litigation where a cost award was made against them.

Eligibility

The ‘eligibility’ criteria are the qualifying criteria for entry as a visitor. The principle requirements are set out at paragraphs V4.2-V4.3 of Appendix V:

Genuine intention to visit

V 4.2 The applicant must satisfy the decision maker that they are a genuine visitor. This means that the applicant:

(a) will leave the UK at the end of their visit; and

(b) will not live in the UK for extended periods through frequent or successive visits, or make the UK their main home; and

(c) is genuinely seeking entry for a purpose that is permitted by the visitor routes (these are listed in Appendices 3, 4 and 5); and

(d) will not undertake any prohibited activities set out in V 4.5 – V 4.10; and

(e) must have sufficient funds to cover all reasonable costs in relation to their visit without working or accessing public funds. This includes the cost of the return or onward journey, any costs relating to dependants, and the cost of planned activities such as private medical treatment.

Funds, maintenance and accommodation provided by a third party

V 4.3 A visitor’s travel, maintenance and accommodation may be provided by a third party where the decision maker is satisfied that they:

(a) have a genuine professional or personal relationship with the visitor; and

(b) are not, or will not be, in breach of UK immigration laws at the time of decision or the visitor’s entry to the UK; and

(c) can and will provide support to the visitor for the intended duration of their stay.

The two main criteria are basically being a genuine visitor, rather than a person who wants to live in the UK, and being able to afford the visit. These criteria should objective but in reality they allow visa officials a LOT of scope for refusing applications on the basis of very subjective opinions.

What does the visit visa guidance say?

[ebook 14398]The Home Office provides guidance to the immigration officials who make visit visa decisions. The following factors are listed to help officials assess whether or not an applicant is ‘genuine’ in their desire to visit the UK, including:

- their previous immigration history, including visits to the UK and other countries

- the duration of previous visits and whether this was significantly longer than they originally stated on their visa application or on arrival

- their financial circumstances as well as their family, social and economic background

- their personal and economic ties to their country of residence

- the cumulative period of time the applicant has visited the UK and their pattern of travel over the last 12 month period, and whether this amounts to ‘de-facto’ residence in the UK

- whether, in your judgment, the information and the reasons for the visit or for extending their stay provided by the applicant are credible and correspond to their personal, family, social and economic background

These factors concern an applicant’s personal circumstances. In addition to these factors, however, other information that is considered relevant in an assessment of an applicant’s intention includes the situation in their country of residence. The guidance states that

where publicly available information indicates that the political and/or economic and/or security situation in the country… is a conflict zone because it has significant political or social unrest, this will form an important part of the assessment of whether the applicant is a genuine visitor;

for example, where information indicates that the country or part of a country is a conflict zone, this information, if it is not outweighed by the particular circumstances of the applicant – for example, that they also have legal right to reside permanently in another, more stable country – can be sufficient reason for you not to be satisfied that the applicant is a genuine visitor

This guidance essentially permits officials to prevent visits by applicants based in conflict zones if they have the right to reside only in the country affected by the conflict. This is seen in practice with the steady increase in the overall visa refusal rate for countries such as Syria, as previously reported by Free Movement. Another important factor that officials considering these applications are permitted to take into account includes:

information on immigration non-compliance by individuals who applied for a visit visa from the same geographical region as the applicant – this can include published statistical information on immigration non-compliance and any other locally held information – Home Office published statistical reports may help with your assessment

It is not clear exactly which ‘statistical information’ is referred to here, and the guidance contains a link to the general Home Office statistics page. It appears to suggest that if an application is made from a certain region where individuals have been granted visit visas in the past and who then failed to comply with the conditions of their leave (for example by overstaying, or working), then this information can be legitimately taken into account when deciding whether a new applicant (with no such adverse immigration history) is a ‘genuine’ visitor.

Do visa officers apply the rules and guidance?

As can be seen from the guidance set out above, ECOs have a wide margin of discretion as to whom they decide to grant visit visas.

A relatively recent report from the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) of the Amman Visa Section in Jordan is not encouraging. Over 10% of decisions made by officers were ‘not reasonable’ as they overlooked or misinterpreted evidence. The report also found that 43% of refusal notices were ‘not balanced’, failing to show that consideration had been given to both positive and negative evidence.

In an older report dating to 2014, the Inspector found that 30% of sampled cases failed decision-making quality indicators. In 22% of cases visa officers failed to consider positive evidence that might assist the applicant, in 10% of cases the visa officer misinterpreted evidence and in 8% of cases visa officers refused visit applications because the applicant had failed to provide a document which was not a document actually asked for anywhere as part of the application process. There was wide variation between different countries and these were average figures.

We do not have statistics about the precise bases for the refusal of visit visa applications. However, it seems safe to assume that the most relevant factor (on an individual basis) is whether or not an applicant has a genuine intention to visit, and in assessing this, his or her ties to their country of residence. This will require consideration of an applicant’s personal circumstances, including employment and family situation.

It is also clear that the Home Office places significant weight on the country situation, as reflected by the high visa refusal rates in conflict zones.

How can you increase your chances of success?

[application]The ECO will be asking whether an applicant has a good reason to return to their home country. The strength of the evidence provided in relation to this area of the application will be key in determining its outcome.

The Home Office provides guidance to applicants as to what type of documents they might submit. In order to demonstrate that applicants in full time work or study might be more likely to return after their visit (and are therefore genuine visitors), the guidance suggests that evidence of such full-time employment or full-time of study should be provided. Letters should be submitted from the relevant institutions on headed paper, and provide as much detail as possible on the nature of the applicant’s engagement (either work or study) in the home country.

The stronger the evidence of the tie to the home country, the more likely an ECO will be persuaded that the applicant will leave at the end of the visit to resume the activity.

In order to demonstrate that an applicant has the means to support him or herself during the course of the trip, the guidance suggests that financial documents are submitted, clearly showing access to the required funds, such as bank statements and proof of earnings such as a letter from an employer confirming the applicant’s employment details (e.g. start date of employment, salary, role, company contact details).

It is possible to receive financial support from a third party (who is legally in the UK), and if this is the case then the third party should submit documents to show they have sufficient resources to support the applicant in addition to themselves and any dependant family. If the third party has previously sponsored visitors who have complied with the terms of their visa then this would also be useful evidence to provide in the form of a covering letter from them, with details of the previous sponsored visits.

If the applicant has a good travel history – e.g. has previously complied with UK visa conditions, as well as immigration requirements in other developed countries (the guidance suggests ‘USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Schengen countries or Switzerland’) – then this will be something to make clear in the application. The guidance on documentary evidence suggests that previous passports (in addition to the current one) might be supplied to demonstrate this past compliance.

What should I do if I am refused a visit visa?

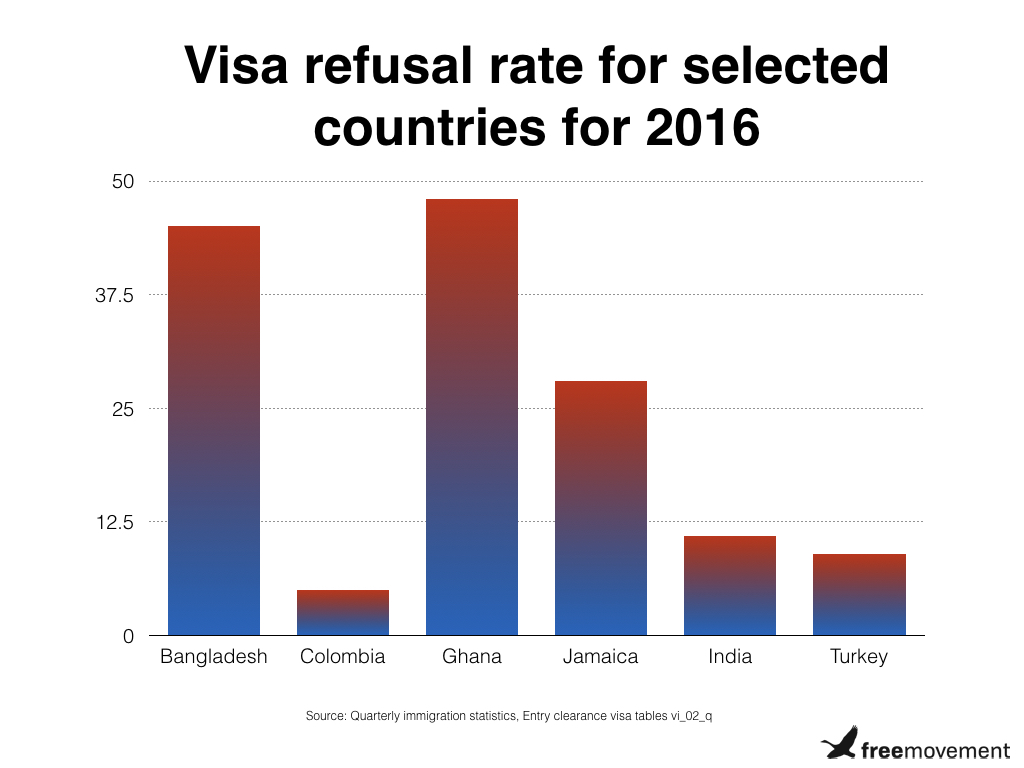

Visa refusal rates are very high for some countries and the fact is that, statistically speaking, there is a higher risk of refusal if you are applying from such a country. By following the advice above, you can hopefully reduce the chance of refusal. But refusal is always a risk.

In the event of a rejected application, there is only a right of appeal before a tribunal in very limited circumstances, where the application might be said to have raised human rights issues. The difficulties of this process, including the length of time it takes, have been set out previously on Free Movement.

Another option is a request for an internal review of the decision taken by the ECO by the Entry Clearance Manager (ECM). However, as reported by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI), the error rate in decisions made by ECMs in a sample of family visit applications from Amman, Istanbul and Pretoria, approached 20%.

The only other way of challenging a refusal decision is by applying for Judicial Review. However, this is an increasingly costly endeavour, and should only be recommended where serious consequences have flowed from the decision to refuse the visit visa (for example, a finding by the ECO that a forged document has been submitted), which could have an impact on future applications.

This was the case in Naidu (the facts of which are summarised at the end of this article, and reported in full here), where Mr. Naidu was accused by the ECO of submitting a forged document and was subsequently banned from entry to the UK for 10 years. It took almost 2½ years for Mr. Naidu’s case to wend its way through the court system, eventually arriving at the Court of Appeal where he received relief (of sorts) in the form of an order for the Entry Clearance Post to reconsider the decision.

In most other cases, avoiding the expense and increasing delays of the tribunal system, the most effective strategy is to simply re-apply, making efforts to remedy whatever defects were identified in the written refusal that is issued by the ECO. This was the course of action taken by Andeel, the Egyptian scriptwriter and cartoonist quoted at the beginning of this piece. He was eventually permitted to visit his wife’s grandmother at the third time of asking, following two refused applications and, as he details in his article, was able to discover Stewart Lee as a result.

Although Mr Naidu made a further application for a visit in January 2014 with much more information about his ownership of the business and the purpose of his visit to the UK, and attempted to clarify the misunderstanding caused by his previous evidence. However, this was not considered by the Entry Clearance Officer, as Mr Naidu was deemed to have previously attempted to deceive the UK immigration authorities and this led to an automatically imposed 10 year ban on re-entry.

The only way that Mr Naidu could challenge the decision to refuse his application and to exclude him for 10 years was via Judicial Review. His initial application to the Upper Tribunal was dismissed as totally without merit, before he appealed again to the Court of Appeal. Following this hearing, the original decision to bar him from entry was set aside and remitted back to the Secretary of State. The court ordered that the Home Office remake its decision, but this time taking into account the material submitted in the second application which had previously been ignored.

With an average 15% refusal rate for visitor visa applications, and a drastic reduction in the availability of remedies for rejected applicants, the importance of getting the application right first time cannot be overstated.

With thanks to Nick Nason for his help with this blog post

SHARE

One Response

Just to add that the financial information – payslips, bank statements etc, must all be consistent, or a detailed explanation given as to why they are not, and all deposits in the bank accounts must be explained and evidenced. Applicants are given no opportunity to provide further information about any anomalies found by the ECO, so need to get this right at the application stage.