- BY Colin Yeo

Shamima Begum loses case in Supreme Court

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Shamima Begum has lost her case in the Supreme Court. This means that she will not be able to return to the UK to argue her main case about whether she should or should not be deprived of her British citizenship. But her main case remains outstanding — and may remain outstanding for a very long time to come, as we will see. The Supreme Court reaches no conclusions here on the final outcome.

Background

Sometimes described as the “ISIS bride”, Ms Begum left the United Kingdom as a 15-year-old schoolgirl to travel to Syria and marry an ISIS combatant. On 19 February 2019, Home Secretary Sajid Javid made a decision depriving Shamima Begum of her British citizenship, which she had held since her birth in the UK. The order was made on the grounds that it was conducive to the public good and Ms Begum held Bangladeshi nationality through her parents and therefore would not be left stateless.

The Supreme Court judgment involves three sets of legal challenges all joined together. One was to a decision by the Special Immigration Appeals Commission, the tribunal which hears immigration cases involving national security issues. SIAC had held that the deprivation decision was not made in breach of the government’s human rights policy, and that although Ms Begum could not have a fair and effective hearing, that did not mean her appeal should automatically succeed.

Importantly, no decision was made by SIAC on the substance of whether Begum should or should not be deprived of her British citizenship. The second and third set of proceedings were about whether Ms Begum should be granted permission to return to the UK to argue the substance and merits of her citizenship case. The Court of Appeal had found that she should.

Today’s decision

The Supreme Court has held that Ms Begum cannot return to the United Kingdom to argue her main appeal. In doing so, the court severely curtails the grounds on which an appeal against deprivation of citizenship may be brought. Such a challenge may only be brought on narrow public law grounds, not on the merits of the decision. However, where a breach of human rights is argued then the review is on the merits. That was not the case here, as Ms Begum’s counsel apparently put the case purely on the basis of common law (paragraph 107). This decision on jurisdiction also dealt with the challenge to the human rights policy. By its very nature, that policy went above and beyond the bare requirements of the Human Rights Act 1998 (paragraph 117) and therefore was not justiciable in this case.

One suspects that the conclusion on jurisdiction is bad news for Ms Begum’s ultimate prospects of success, should she ever get the chance to argue her main appeal. It prevents her arguing that Sajid Javid was wrong and that it is actually not conducive to the public good for her to be deprived of her citizenship. There is still scope to argue that the Secretary of State misunderstands the true meaning of “public good”, though, which in previous legislative iterations of the citizenship deprivation power acted as a constraint on the power to deprive, not the gateway. For immigration lawyers reading this, this is the Supreme Court coming down in favour of the Pirzada/Ockelton line of thinking, not the Deliallisi/Lane line of cases.

On the issue of what should happen in an appeal where one of the parties is unable to participate, the Supreme Court holds that the appeal should not automatically succeed:

The fact that the appeal process is a safeguard against unfairness does not means that a decision which cannot be the subject of an effective appeal is unfair.

It would in fact be “fallacious” to argue otherwise, says Lord Reed, and it would be unjust to the respondent if the appeal automatically succeeds because the appellant finds herself unable to present her appeal effectively.

What seems to me to be missing from the reasoning here is recognition that the reason Ms Begum cannot effectively participate in her appeal is because of the actions by the other party to the appeal in depriving her of citizenship while she was outside the country and then refusing her re-entry. Although no doubt the respondent would retort that Begum brought this on herself. As a 15-year-old schoolgirl.

The Court of Appeal is heavily criticised for stepping in and assessing national security risk for itself: it “appears to have overlooked the limitations to its competence, both institutional and constitutional, to decide questions of national security”. It was “in no position either factually or jurisdictionally” to undertake a comparison with other supposedly like cases. There was “no evidence before the court from the police, Crown Prosecution Service or Director of Public Prosecutions as to whether it was either possible or appropriate to ensure that Ms Begum was arrested on her return and charged with an offence”. Nor was there any evidence as to whether she might be remanded in custody, or whether a “TPIM” counter-terrorism order would be imposed on her.

This puts me in mind of Sajid Javid’s press statement at the time of the Court of Appeal judgment, for which he was roundly criticised in legal quarters.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s judgment reads as a deliberately very narrow one. This is hardly surprising in the current highly politicised circumstances, but it is disappointing for public lawyers and perhaps public law. General principles are where possible eschewed and the case is not sent back to be re-heard on any of the arguable points.

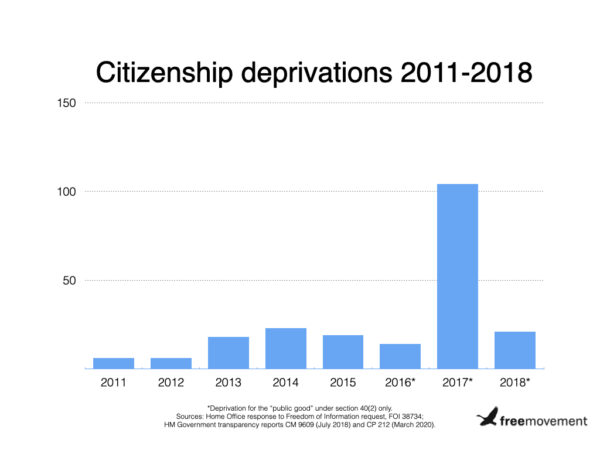

Ms Begum is now faced with the choice of instructing her lawyers to try and proceed as best they can with the main appeal against losing her citizenship, or waiting — potentially indefinitely — until she is able to participate meaningfully from abroad. She may not be the only person in this unenviable position, as our updated chart of known citizenship deprivation decisions shows. Use of this power was virtually unknown before 2010.

SHARE

5 Responses

“For immigration lawyers reading this, this is the Supreme Court coming down in favour of the Pirzada/Ockelton line of thinking, not the Deliallisi/Lane line of cases.”

But what about KV (Sri Lanka), R (On the Application Of) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 2483?