- BY Iain Halliday

What’s going on with UK visit visas?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

In short: the Home Office are frequently refusing them. This may not come as a surprise to immigration lawyers, who are all too familiar with the Home Office’s culture of disbelief, but it has come as a nasty shock to many artists, authors, and performers refused entry to the UK recently.

The Radio Times reported last month that

securing visas to enter the UK and play at the world music festival Womad is now proving ‘so difficult and humiliating’ that acts are turning down organisers’ invitations and staying away.

The story was also reported by the Guardian, the Independent, the Times, and the BBC. This was followed by reports last week that a dozen authors who were planning to attend the Edinburgh International Book Festival have had their visas refused. According to the festival’s director, speaking to the Guardian:

It is Kafkaesque. One was told he had too much money and it looked suspicious for a short trip. Another was told she didn’t have enough, so she transferred £500 into the account – and then was told that £500 looked suspicious. It shouldn’t be the case that thousands of pounds should be spent to fulfil a legitimate visa request. I believe this is happening to many arts organisations around the country, and we need to find a way around it.

The story was also covered by the Scotsman, ITV, and BBC Radio Scotland.

So what’s going on?

Good in theory: the visit visa rules

The visit visa rules are contained in Appendix V of the Immigration Rules. They are uncontroversial. A visitor must satisfy the Home Office that they:

- will leave the UK at the end of their visit;

- will not live in the UK for extended periods or make the UK their home through frequent or successive visits;

- are genuinely seeking entry for a purpose that is permitted by the visitor routes, such as tourism, certain business activities, carrying out a permitted paid engagement, or performing at a permit free festival;

- will not undertake any prohibited activities such as working, studying, or receiving payment from a UK source; and

- have sufficient funds to cover all reasonable costs in relation to their visit without working or accessing public funds.

Womad is a “permit free festival”. Festivals can apply to become part of this list each year. Performers seeking entry to attend a festival that is not on this list (such as the Edinburgh International Book Festival) must meet the permitted paid engagements rules. There are five types of permitted paid engagements:

- highly qualified academics invited to examine students and/or participate in or chair selection panels;

- experts invited to give lectures in their subject area;

- overseas designated pilot examiners invited to assess UK based pilots;

- qualified lawyers invited by a client to provide advocacy for a court or tribunal hearing, arbitration or other form of dispute resolution for legal proceedings within the UK; and

- professional artists, entertainers, musicians or sports persons invited by a UK based creative or sports organisation, agent or broadcaster to carry out an activity directly relating to their profession.

All fair enough, really. The rules are not the problem.

Poor execution: the Home Office’s application of the rules

The problem is with the Home Office’s application of these rules. Often decision-makers simply don’t believe that the person seeking entry is a genuine visitor, instead assuming that they intend to remain in the UK permanently.

To be fair, some people do breach the terms of their visit visa and remain in the UK, claiming asylum or applying to stay in the UK under human rights law. There is, after all, no way to claim asylum from outside the UK. But the recent difficulties faced by artists and authors seeking entry to the UK to attend well-established international festivals suggests the Home Office is adopting an excessively restrictive approach.

A person’s intention is a difficult thing to judge. It is a delicate balance. On the one hand, there is a legitimate need to prevent abuse. On the other hand tourists, family and friends of UK residents, performers, musicians, authors, and sportspeople all need to be able to visit the UK. Even apart from the human aspect — imagine being told you can’t come to visit your granddaughter — making it difficult to run a music or literary festival in the UK does nothing for the economy. In-demand artists will simply accept the invitation from New York or Dubai instead.

Are decision-makers striking the right balance? In my experience, the scales are usually weighted against visit visa applicants. Often it feels like applicants are guilty until proven innocent. Everything is treated with suspicion.

[ebook 14398]I advise clients to submit extensive documentary evidence of their social and economic connections in their country of origin in order to demonstrate that they will return after their visit to the UK. Where the documents could give rise to questions, additional evidence should be provided e.g. bank statements from your savings account to show where that recent deposit into your current account came from, a letter from your employer confirming why there is a small discrepancy between the amount shown on your payslip and the money deposited in to your bank account, a letter from your landlord confirming that you reside at their property through an informal arrangement and there is no written tenancy agreement which can be produced. Failure to provide these sorts of explanations can be fatal to the application.

The result: an unworkable system

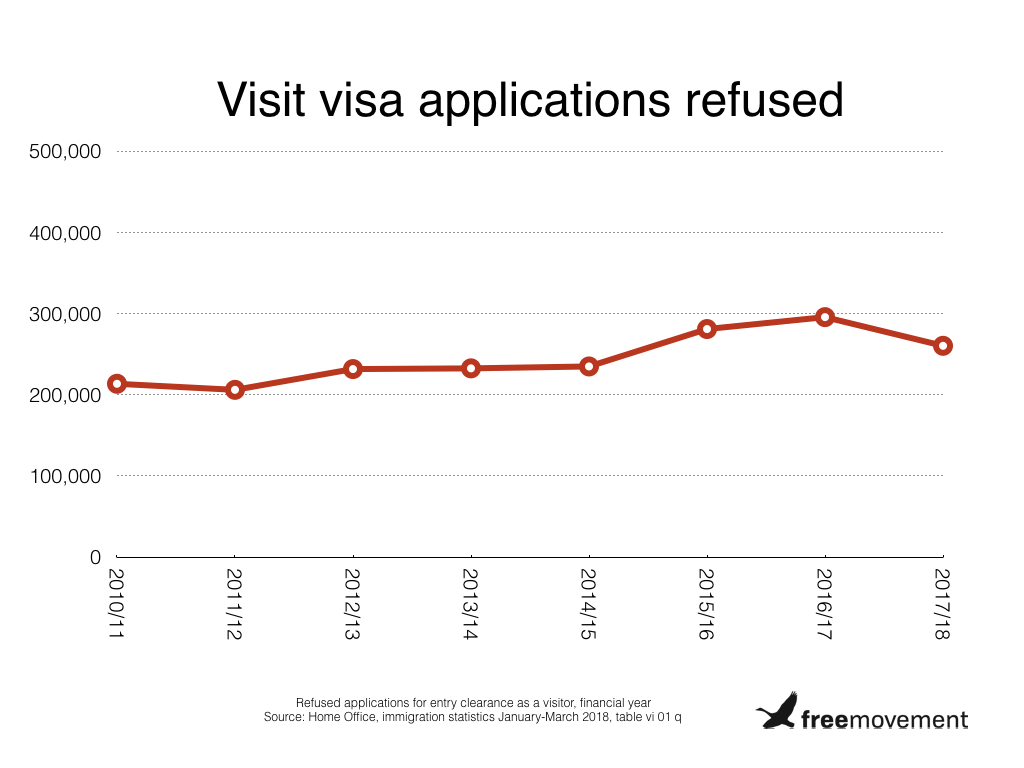

Many applicants do not realise such extensive evidence is necessary. Last year, 260,000 visit visa applications were refused. The rate of refusal is fairly steady over time, but varies significantly by nationality: over one third of all potential visitors from Pakistan, for example, were turned away. It is hard to believe that all of these applicants were hell bent on abuse of the system.

There is generally no right of appeal against refusal of a visit visa. An appeal can only be lodged on human rights grounds and is usually only possible where a person is applying to visit close family. This gutting of appeal rights, back in 2013, coincided with an sharp increase in family visit visa refusals.

Without a mechanism to challenge visit visa decisions, there is no oversight or accountability. Officials can do what they like. Are they applying the rules correctly? Have they properly taken into account all evidence submitted? Are they refusing visas on the basis of irrelevant issues? Are their decisions reasonable? Who knows? There’s no external quality control aside from the occasional reports of the immigration inspector, who last time out found that over 40% of refusal notices were “not balanced, and failed to show that consideration had been given to both positive and negative evidence”.

The lack of appeals leaves judicial review as the only remedy. This is very expensive. The cheaper and easier option is to re-apply, this time providing extensive documentary evidence to show that you are a genuine visitor (and providing additional documentation to address any issues raised in the refusal). Providing such evidence and making multiple applications becomes the norm, without anyone at any point considering whether this is sensible or desirable.

Unfortunately, many simply aren’t willing to go to such lengths to visit the UK:

One author… wanted to back out at that point because he couldn’t bear it, but we asked him to continue (Nick Barley, director of Edinburgh International Book Festival, speaking to the Guardian)

It’s too difficult and too expensive, and it’s humiliating (Chris Smith, director of Womad, speaking to the Radio Times)

It is not really worth coming any more (manager of an African music group speaking to the Guardian)

With the government ploughing ahead with Brexit under the slogan “Global Britain“, the Home Office line is that “we welcome artists and musicians coming to the UK from non-EEA countries to perform”. It doesn’t exactly look like it.

SHARE