- BY Colin Yeo

British by descent: when the child of a British citizen is not themselves British

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleA child born abroad to British citizen parents who were themselves born abroad is not automatically British at birth. While this might be no shock to immigration lawyers, occasionally the story of a family finding out their child is not British in these circumstances will make headlines.

One such example was two-year-old Lucy, a child of British parents who was told by the Home Office that she must leave the UK. It is always difficult to comment on news stories without knowing the full facts but it is certainly true that British citizenship can only be passed down a certain number of generations to children born outside the UK. Of course, that is no excuse for writing to a toddler to tell them to leave the UK, particularly when the same toddler might well be eligible to become British by being registered as a British citizen.

In this post, we’ll explain how it is that a child born to British parents might not be British herself, and what can be done about getting her citizenship. It is partly adapted from our training materials on British nationality.

Acquiring British citizenship

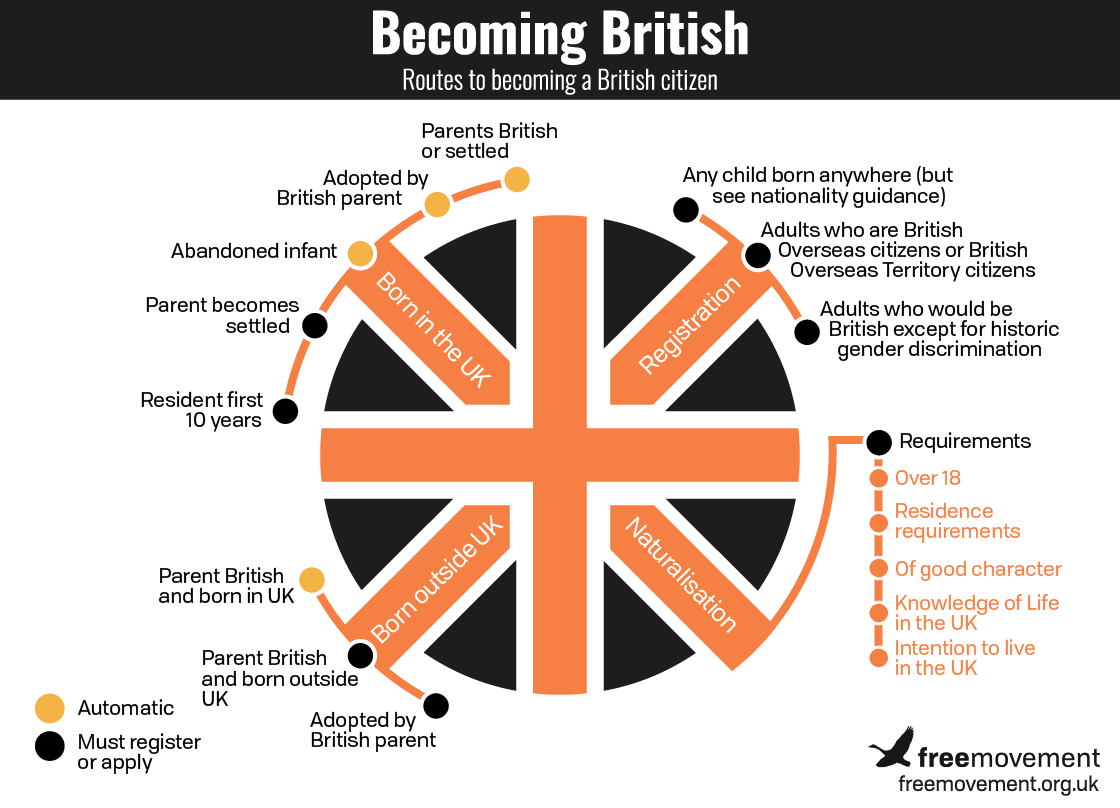

There are lots of ways to become British, as our infographic below shows. The vast majority of British citizens have acquired their citizenship automatically by birth. We also sometimes call this way of becoming British “by operation of law” because it happens automatically under the British Nationality Act 1981 without the parent or child having to do anything.

A child can be born British by operation of law in one of two ways:

- by birth after 1 January 1983

- by section 11 of the 1981 Act, which ensured that most Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies with a right of abode automatically became British citizens on 1 January 1983

Those who acquire British citizenship automatically don’t need to apply for British citizenship; you cannot apply to become something you already are.

That said, proof that a person meets the criteria for automatic acquisition may be required in order to prove citizenship and to obtain a British passport. Typical proof would include the child’s full birth certificate (not an abbreviated version) showing the parent(s)’ names and evidence of either the child’s mother or father’s settled immigration status or British citizenship at the time of the birth.

Example

Clare was born in the UK in 2010. Her father, Colin, is a British citizen so Clare was automatically born a British citizen. She has never travelled abroad and Colin has not applied for a passport for her yet. If or when he does apply for a passport for her (or if or when she does herself as an adult) he will need to submit proof that she qualified for British citizenship at the time of her birth.

Birth within the United Kingdom

Since 1 January 1983, being born in the UK is not by itself enough to be automatically born British. At least one of the child’s parents must also be settled in the UK at the time of birth.

Section 1(1) of the British Nationality Act 1981 says:

A person born in the United Kingdom after commencement, or in a qualifying territory on or after the appointed day, shall be a British citizen if at the time of the birth his father or mother is–

(a) a British citizen; or

(b) settled in the United Kingdom or that territory.

“Settled in the United Kingdom” is defined in section 50 of the 1981 Act as:

being ordinarily resident in the United Kingdom or, as the case may be, in that territory without being subject under the immigration laws to any restriction on the period for which he may remain.

Effectively this means that the parent in question must have a settled immigration status, such as:

- indefinite leave to remain, including settled status under the EU Settlement Scheme

- the right of abode, or

- permanent residence under EU law if the child was born on or before 30 June 2021.

It would not be enough, however, to be born to a parent living in the UK with a visa which grants only limited leave to remain. Children born to such parents are not automatically British citizens.

There are also special rules on children born before 1 July 2006 to an unmarried British father, for children of members of the armed forces, for adopted children and for abandoned children, which we will not go into here.

Birth outside the United Kingdom

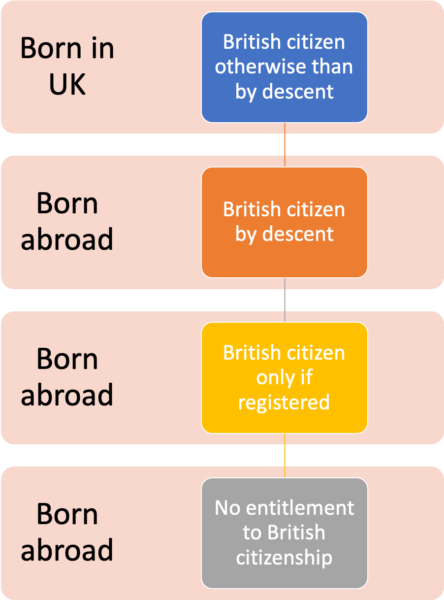

Acquiring citizenship by birth in the UK is an example of what is called British citizenship “otherwise than by descent”. We can skip the full details of what that means. What matters is that a British citizen “otherwise than by descent” can have a child outside the UK and the child will automatically be born British “by descent”.

A British citizen by descent cannot automatically pass citizenship to a child born outside the UK. This seems to be what has happened with two-year-old Lucy, who was born in South Africa to British citizens by descent. The legal reason for it is section 2 of the 1981 Act:

(1) A person born outside the United Kingdom and the qualifying territories after commencement shall be a British citizen if at the time of the birth his father or mother—

(a) is a British citizen otherwise than by descent…

There is a more detailed definition of who is a British citizen by descent in section 14 of the 1981 Act.

If the child of a British citizen by descent is born outside the UK, the child can become British after birth by being registered. We look at this possibility below. If the child is not registered, though, the child will not become British.

In other words, the first generation born abroad is born British, the second generation born abroad can become British by being registered, but the third generation cannot become British, at least through their parentage.

Ultimately, it makes sense that a form of citizenship will only be passed down a certain number of generations. At the time of the introduction of the British Nationality Act 1981, Thatcher’s government intended for citizenship to be passed down a further generation. This part of the legislation was amended as the Bill passed through Parliament. The government as a consequence introduced the UK Ancestry visa to enable work then settlement in the UK for those who had a grandparent born in the UK. But that is not much help to a toddler, because applicants must be aged 17 or over.

Applying for registration for a child born outside the UK to British by descent parents

Registration by entitlement

A child born abroad to British by descent parents (the yellow box in the flow chart above, and reportedly little Lucy’s situation) may be entitled to registration as a British citizen under sections 3(2) or 3(5) of the 1981 Act.

Registration under section 3(2) requires one of the child’s parents to be British by descent and to have lived in the UK for a continuous period of three years (with 270 absences from UK allowed during that period) at some point prior to the child’s birth. That parent must also have a British citizen otherwise than by descent parent (i.e. the child’s grandparent must be British otherwise than by descent). If a child meets the criteria set out in section 3(2) then the child will be entitled to be registered as a British citizen by descent.

Registration under section 3(5) seems very similar to section 3(2). But under section 3(5), the relevant three-year period of residence in the UK must have occurred at some point after the child’s birth and must include not just the British by descent parent but also the child.

This will generally require the child to have moved to the UK with the parent and have a visa during this time. There is however no requirement for the child to have a British otherwise than by descent grandparent. If a child is registered under this rule, the child will become a British citizen otherwise than by descent, so, if the facts of the case allow it, objectively this is a better option.

Registration at Home Secretary’s discretion

If a child doesn’t fit into the section 3(2) or section 3(5) criteria, it is still possible to apply under section 3(1) of the 1981 Act for the child to be registered as British at the discretion of the Home Secretary. In this section we’ll give an overview of how that works, but if you are reading this and thinking about applying for your own child, just be aware that it’s a complex area and reading the full policy referred to below and/or instructing a lawyer to help might be wise.

Unlike the other registration applications, there is no entitlement to registration under section 3(1). Such an application involves putting a case to the Home Office and asking for the child to be made British. A very wide discretion is afforded in these cases and all cases will be considered on individual merits, but generally that discretion will be exercised in line with published policy.

Caseworkers considering discretionary applications under section 3(1) must take into account the child’s:

- future intentions

- parents’ circumstances

- residence in the UK

- immigration status

- any compelling compassionate circumstances raised as part of the application

Going back to Lucy’s case again, let’s say for example that she were ineligible to apply under section 3(2) but is considering section 3(1). With a two-year old child brought to the UK as a visitor by British by descent parents, a caseworker considering whether or not to exercise discretion to register the child will be particularly interested in the child’s immigration status. The policy states that

…we would normally expect the child to have become settled in the UK before applying for British citizenship. This is because a child’s future can clearly be seen to lie in the UK if they are not subject to immigration time restrictions. It is also consistent with other routes based on residence in the UK, in which a person is expected to follow a path through settlement to citizenship.

This will normally mean that the child has indefinite leave to remain under the immigration rules.

If the child is not settled in the UK, you must consider whether there is compelling evidence to show that:

- the child’s future clearly lies in the UK

- the benefit to the child of becoming a British citizen at the current time outweighs the normal expectation that a person becoming a British citizen should be settled here – (a child does not need to be a British citizen to access education or health care in the UK, but there may be other factors that mean it is important for the child to become British now)

Being free from immigration restrictions will be less important where one or both parents are British citizens who have come to the UK to live permanently and:

- the child satisfies the other expectations for registration

- the parents meet the expectations with regard to their circumstances

So registration is clearly not a foregone conclusion in cases like this, even where both parents are British. Registration under section 3(1) doesn’t exist to enable circumvention of the usual expectations for citizenship set out above. The cynical amongst us might say that the Home Office would like to receive its hefty £3,029 indefinite leave to remain fee first before allowing the family to fork out the registration fee of £1,214 as well.

If a child were to be successfully registered under section 3(1), if one or both of its parents were British at the time of the child’s birth, the child will be a British citizen by descent. In all other cases the child will be otherwise than by descent.

The published policy also covers a very wide array of other circumstances in which children can be registered under section 3(1), including adopted children, children born to a parent registered under section 4C, 4G, 4H, 4I or 4L of the 1981 Act, and children of unmarried partners. We won’t cover those here, but would just repeat the caveat that all this can be fairly complicated and this post doesn’t capture every detail.

How to submit an application for registration

An application for registration is usually made online but can also be made by submission of a paper application on Form MN1. The application can be made from both inside and outside the UK, though in the case of children applying under section 3(1) it is likely to be an issue if the child is not already in the UK, due to the expectation that a child seeking registration will normally have completed a period of residence in the UK.

Applications under sections 3(2) and 3(5) have specific evidence that must be submitted, whereas applications under section 3(1) are a lot more freeform, with the onus, as always, being on the applicant to make their case. In section 3(1) cases, applicants should read through all of the Home Office’s published policy very carefully and perhaps consider taking specialist advice before proceeding, because at a non-refundable £1,214, registration applications do not come cheap.

However, for families who are unable to afford the fee it is possible to apply for a fee waiver for registration applications. We have a useful explainer on fee waiver applications here.

What if none of the registration options are suitable?

There will be times where none of the registration options are suitable and none will lead to British citizenship for the child. In those cases, where the parents are British by descent, it will normally be possible to apply for indefinite leave to enter the UK if the child is abroad, or indefinite leave to remain in the UK if the child is in the UK. Such applications are made under paragraphs 297 or 298 of the Immigration Rules.

This article was originally published in October 2019, with thanks to John Vassiliou for his input. It has been updated by Rachel Whickman so that it is correct as of the new date of publication show.

SHARE