- BY Fahad Ansari

The Home Secretary can legally deprive Shamima Begum of her citizenship – but he shouldn’t

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

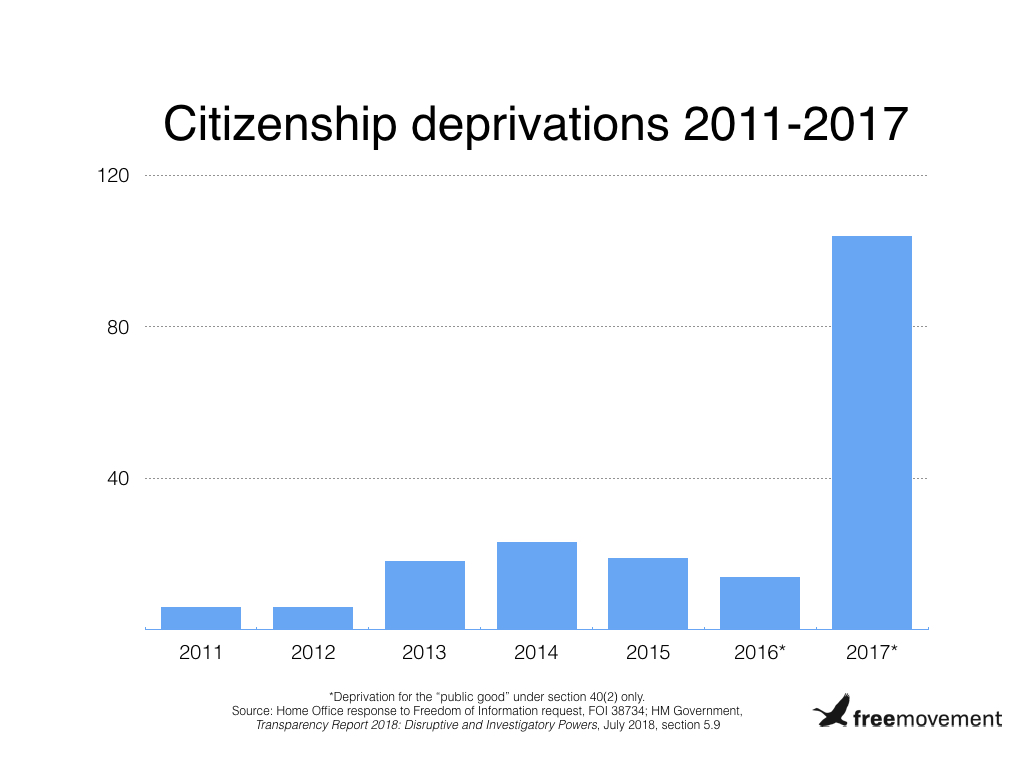

The UK government did not begin its deprivation of citizenship policy yesterday, when Home Secretary Sajid Javid signed an order stripping Shamima Begum of her British nationality. The deprivation of citizenship power has been increasingly used in recent years, with 104 citizens deprived of their British nationality in 2017 alone. Those deprived include aid workers and a man who went abroad to support his wife who was giving birth.

But it is unlawful to deprive someone of their citizenship if this would render them stateless. Making someone stateless is denying them the right to have rights (as the philosopher Hannah Arendt once put it).

The law on British-Bangladeshi dual nationals

In the case of UK citizens of Bangladeshi heritage, like Begum, Bangladeshi law states that they automatically have Bangladeshi citizenship on birth. They are dual nationals. However, if they do not make an active effort to retain that citizenship, it lapses when they reach the age of 21.

Such was the case with E3 and N3, two British citizens of Bangladeshi origin who found themselves deprived of their citizenship when they were abroad in Bangladesh and Turkey respectively. The Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) ruled in E3 & N3 (Exclusion : Preliminary issue) [2018] UKSIAC SC_146_2017 that as they had not sought to retain their Bangladeshi citizenship before they turned 21, it had automatically lapsed. As a result, the decision to deprive them of their UK citizenship had rendered them stateless and their appeals against deprivation were allowed.

In Shamima Begum’s case, my understanding is that she is British born and raised and has never been to Bangladesh. Nevertheless, it may be that as she is still under 21, her Bangladeshi citizenship technically remains intact. So she is not stateless by law. It does not matter if she does not hold a Bangladeshi passport, as holding a passport is distinct from the legal fact of citizenship.

Sajid Javid was no doubt aware of the ruling in E3 and N3. The bizarre result is that young people like Begum are more vulnerable to deprivation than mature adults aged over 21.

Whatever the strict legal position, it is virtually impossible for Begum to obtain evidence of her Bangladeshi citizenship or use a single benefit of citizenship in any way. She is in a refugee camp in a war zone. She has no consular access to the Bangladeshi authorities. For all intents and purposes, she is de facto stateless.

A closed appeal suits the authorities

Of course, Ms Begum’s appeal against the decision is not just limited to the statelessness argument. She can also argue that the decision is disproportionate and that there were less punitive measures available to achieve the objective of safeguarding national security.

We have over a dozen counter-terrorism acts on the books in this country criminalising even travel to Turkey if it is with the intention to go into Syria — even if you don’t get on the plane to Istanbul. Why is the UK so afraid of prosecuting Begum in open court?

The argument in her case (and in all deprivation cases) is that either there is insufficient evidence to sustain a successful prosecution, or that the evidence is not disclosable in open court as it would compromise intelligence sources. But if there is insufficient evidence to prosecute such people in open court, then how on earth can they be sanctioned with the severest penalty without any form of due process?

The Home Office would much rather deprive them of their citizenship and thereafter defend their decisions, not in open court, but in the mysterious world of the Special Immigration Appeals Commission. SIAC is the judicial body which routinely decides these appeals. A large part of the allegations and evidence is presented to the judge in closed proceedings, meaning that neither the appellant nor his instructed lawyers are permitted to see it or even know about it, let alone try to challenge it.

To provide a semblance of due process, security vetted Special Advocates are appointed by the Attorney General to represent the appellant in the closed hearing. But once they see the secret evidence, they are prohibited from communicating with the appellant or his lawyers.

In a case like Begum’s, one would have thought that there was adequate evidence to prosecute her for one of the myriad of offences under our counter-terrorism laws specifically created to deal with returnees from Syria. Yet Sajid Javid has deliberately chosen not to do so.

Deprivation of citizenship: a discriminatory power

While the UK government believes that it has washed its hands of Begum, it does still have a responsibility to her baby. He is a British citizen, having been born at a time when Begum held UK citizenship. Javid needs to declare how he intends to deal with that innocent child.

The power to deprive UK citizens of their citizenship can only be used against the children of immigrant parents — meaning that the application of the policy is inherently discriminatory. It cannot be used on a white English person with white English parents. It is nothing more than a return to the medieval punishment of banishment and exile against those who were always perceived to be “foreign”.

3 Responses

See also

Bangladesh doesn’t want Shamima Begum. Here’s why it might have to take her.

Shamima Begum is not a Bangladeshi citizen.

Moreover, if the Home Secretary’s deprivation order was after Shamima’s baby’s birth, then it’s undisputed that Shamima’s baby is British by descent. Then the UK Government should offer the British baby their full support.