- BY John Vassiliou

What happens if you mistakenly apply for British citizenship instead of indefinite leave to remain?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Page contents

- Making the wrong application

- Leave expired while naturalisation application was being considered

- Application for leave to remain on human rights grounds

- Arrest, detention, removal

- “Case clearly without substance and cannot succeed on any legitimate view”

- Removal averted and human rights appeal won

- Three years of hell for Lucas, at huge cost to the taxpayer

What happens when an American graduate, about to become eligible for indefinite leave to remain having lived lawfully in the UK for almost a decade, incorrectly thinks that he is eligible to apply for British citizenship and applies for that instead?

You might think that, for example, the Home Office would politely tell him “no” but offer to process a different immigration application for him instead. This is, after all, the department that is going to deal with the Brexit-related immigration problems of EU citizens using “common sense” (copyright: Sajid Javid).

Immigration lawyers know that, without profound institutional change, this is a hollow promise. The experience of this client of mine, Lucas, shows how brutally the Home Office routinely treats blameless migrants who end up in its clutches.

It also demonstrates how easy it is to become an “illegal immigrant”. The research consensus is that the majority of people living in the UK without permission have overstayed on their visa, rather than having snuck in. Lucas’s story is a case study in how overstaying can occur even if someone has no intention of letting their visa expire — with all the nasty consequences that follow.

Making the wrong application

Lucas is an American citizen, though he left the USA aged six months when his family moved to the Bahamas for work. He has no close family or friends in the USA. Aged 13, his parents sent him to boarding school in the UK. He arrived here with a child student visa in September 2004. Lucas attended school and university in Edinburgh, spending his teenage and early adult years growing up here in the UK. Nearing the end of his latest student visa in summer 2014, he consulted the Home Office website and sought advice from his university’s international student advisor.

It seemed apparent to them both that Lucas was eligible to apply for naturalisation as a British citizen, having completed over five years of residence here in the UK. What they missed was the crucial requirement that the applicant be free from immigration restrictions for the fifth of those five years. In other words, the applicant must have settled status, indefinite leave to remain or permanent residence for a year before being able to naturalise.

This may seem like an obvious error to legal practitioners, but to non-practitioners, it is a simple mistake to make. Save for that small but significant error, the other vital ingredients of a citizenship application were all there: correct application form valid passport, current visa, Life in the UK test, English language ability, application fee.

Lucas made his application for naturalisation on 14 May 2014, a couple of weeks before the expiry of his visa.

Leave expired while naturalisation application was being considered

An application for further leave to remain made prior to expiry of current leave results in a statutory extension of leave while the application remains pending, under section 3C of the Immigration Act 1971. In other words, you don’t become an “illegal immigrant” if you have applied for a visa extension. This is a long established and sensible principle in immigration law, which bridges the gap between timely submission of one visa application and the months that then pass while the Home Office considers that application.

Section 3C is not however engaged by citizenship applications, and therefore did not apply in Lucas’s case. When Lucas’s leave expired on 31 May 2014, that was it, it ended. Despite no answer having been received on his still pending naturalisation application, he unknowingly, became an overstayer in the UK.

But an application for further leave to remain in the UK and an application for British citizenship are both immigration applications, I hear you say. You are right. And are they not both submitted to the Home Office, the same body that makes the decisions on leave to remain and on citizenship? Right again. In fact, are they often not actually considered in the very same building in Liverpool? Well done, three out of three. That still does not cure the technicality that results in one application statutorily extending leave while the other does not.

So instead of Lucas’s application being promptly returned to him with a refund and a polite explanation that he is not eligible because he needs to first apply for ILR, the Home Office does what it is good at, which is nothing at all. It took eight months for him to receive a refusal of his application with the above explanation, well beyond even the upper six-month limit of the Home Office’s normal service standard and long after his leave had come to an end.

Lucas’s naturalisation application was refused in January 2015.

Application for leave to remain on human rights grounds

[ebook 57266]Had he been advised by a solicitor, Lucas would not have submitted that application for naturalisation. Instead he would have considered other visa options for further leave to remain. He would only have needed to get further leave to remain until September 2014, four months after the expiry of his leave on 31 May 2014 in order to have achieved ten years’ continuous lawful residence in the United Kingdom and thus eligibility for indefinite leave to remain (ILR). He may even have been advised to apply for ILR straight away. Given how long the Home Office takes to make decisions, it is likely that by the time his application was considered he would have completed ten years of continuous lawful residence by virtue of the statutory extension of his leave offered by section 3C.

Lucas instructed my firm in February 2015 and we lodged an application for leave to remain on human rights grounds, explaining the unfortunate sequence of events and Lucas’s background. Regrettably we also had to advise Lucas to immediately resign from his job on the basis that he had no permission to work.

The human rights application was refused, with no possibility for an appeal, in March 2015.

In an effort to generate a right of appeal, we made a further application in October 2015, after the Immigration Act 2014 had come into force. This time we had to seek a fee waiver: Lucas was destitute as a consequence of being unable to work. A number of rejections followed on account of this fee waiver request, until finally Lucas’s friends and relatives were able to scrape together the full fee needed for a valid application to be lodged in March 2016. After an acknowledgment letter on 23 March 2016, there was radio silence.

Arrest, detention, removal

On 12 March 2017, almost one year later, with no notice whatsoever, Lucas was arrested and taken to Scotland’s only immigration detention facility at Dungavel. Thus deprived of his liberty, directions were set for Lucas’s enforced removal from the UK on 15 March at 17:00 hours.

This was a distressing, upsetting and confusing experience not just for Lucas but for us as his representatives. Why would the Home Office do this to him while he has a case pending? Was it really necessary to detain him?

Two days later on 14 March 2017, at 10:45am, we found out that the Home Office had made a decision refusing Lucas’s case on 20 December 2016. They just didn’t actually communicate that to anyone. With little over 30 hours until his removal, I remember having to somehow find available counsel to draft a petition for judicial review. This involved essentially locking an advocate who shall remain nameless into our office with the papers in front of him and a desperate plea to get a petition drafted by the end of the day, so that it could be lodged in court the next morning to prevent removal.

“Case clearly without substance and cannot succeed on any legitimate view”

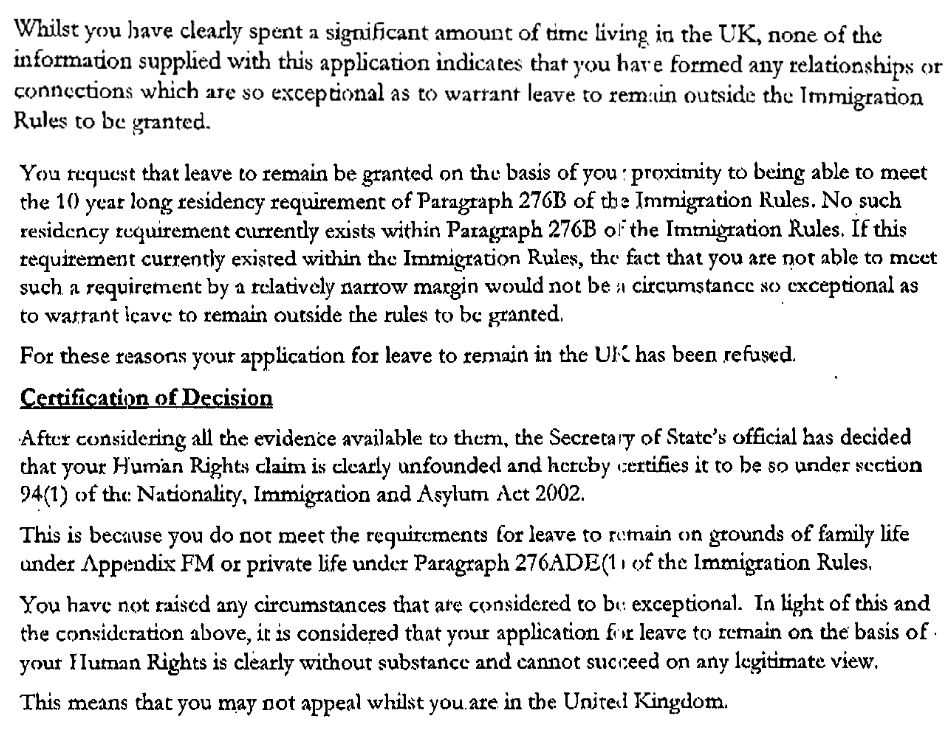

When we got our hands on the Home Office’s December decision letter, it said as follows:

In other words, the Home Office considered that Lucas did not meet the Immigration Rules on private and family life. That he had very narrowly missed out on long residence by submitting the wrong application form was not enough to bring him within those rules either, despite the author’s bizarre denial of the existence of a ten-year long residence route to indefinite leave to remain (I can assure you it does exist). The fact that Lucas had left the USA aged six months and had no connections with that country was not deemed “exceptional” enough to justify an award of leave outside the Rules.

Finally, the effect of certifying the case claim as “clearly unfounded” was that Lucas was deprived of the opportunity to appeal to an independent tribunal from within the United Kingdom. That certification is what we challenged in the judicial review petition. Lodging this petition had the effect of suspending Lucas’s removal from the UK, though the Home Office refused to release him from detention until an immigration judge granted bail.

Removal averted and human rights appeal won

The Home Office vigorously defended the petition for judicial review all the way to a full hearing at the Outer House of the Court of Session (in England I believe this would have been heard at the Upper Tribunal). Lord Brailsford heard the case in August 2017 and allowed the petition. The certification of the case was quashed and the case sent back to the Home Office for a fresh decision.

[application]In October 2017 the Home Office made a new decision, again refusing the human rights case, but this time allowing an in-country appeal. This took place at the First-tier Tribunal in Glasgow in June 2018.

After all that preceded this appeal, the Home Office did not even bother to send a representative to argue the case at the appeal. The appeal was successful and Lucas was allowed to remain in the UK by the judge on human rights grounds. A far cry from being unable to succeed on any legitimate view.

Now, in August 2018, he has received confirmation that his 2.5 year visa is being issued to him. He will have to complete a further ten years of indentured servitude to the Home Office continuous lawful residence in the UK in order to become eligible for indefinite leave to remain again, putting firmly aside any aspirations towards citizenship. This will entail four more visa applications, at a cost of £6,988 (based on today’s prices – these increase annually) excluding any legal fees.

Three years of hell for Lucas, at huge cost to the taxpayer

So what was the impact of all of this on Lucas? He says:

I have essentially had the most important years in my career development taken away from me, and now I more or less have to start over. I am not sure if I will be able to return to my previous employer yet, but I am hopeful. I had a graduate job through university that I enjoyed, and had recently been promoted before this all happened. It has been difficult for me to see all of my friends moving on with their careers, and lives, while I have been stuck in limbo. I am worried that if I am unable to return to my previous job, finding a new job might be awkward, as I will have to explain the large gap on my CV, and it might not help me stand out as a employable candidate.

I have had financial problems the last three years, and it is going to take me a while to get it all sorted even if I am able to find employment immediately. Living with such a low amount of money has been difficult. My diet has been very unhealthy, as I have had to buy the cheapest food I could find. I regularly had to miss social events because I hated having to rely on friends to buy my food/drink/event tickets. I feel that a lot of my friendships have been affected by this. I have missed birthdays, weddings, weekend trips away etc.

All of this has lead to some depression that I hope will go away when my life becomes “normal” again.

The cost to the public purse of running this case? Luckily for him, Lucas was able to get legal aid for the majority of these proceedings. I’d estimate around £19,000 – 20,000 on legal costs taking into account legal aid, Home Office’s legal fees defending the judicial review, and the costs award made against the Home Office in those proceedings. Not to mention the cost of detention and the unquantifiable costs of court and judges’ time. Lucas himself paid around £4,000 in fees before he became destitute but the real issue is the human cost inflicted on him over these past three years.

And for what purpose? Simply because a young man makes a mistake and submits the wrong application on the wrong form? This could all have perhaps been averted had the Home Office been imbued with a culture of common sense and compassion rather than one of “computer says no” hostility.

This, then, is the record of is the organisation that is going to handle EU residents with “common sense” after Brexit. This is why immigration lawyers are profoundly cynical about such pieties. And this is why we will continue to be pessimistic until we see real evidence of the promised change in Home Office culture.

SHARE